LINKED PAPER

Insights on the effect of aircraft traffic on avian vocal activity. Vincelette, H., Buxton, R., Kleist, N., McKenna, M.F., Betchkal, D. & Wittemyer, G. 2020 IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12885 VIEW

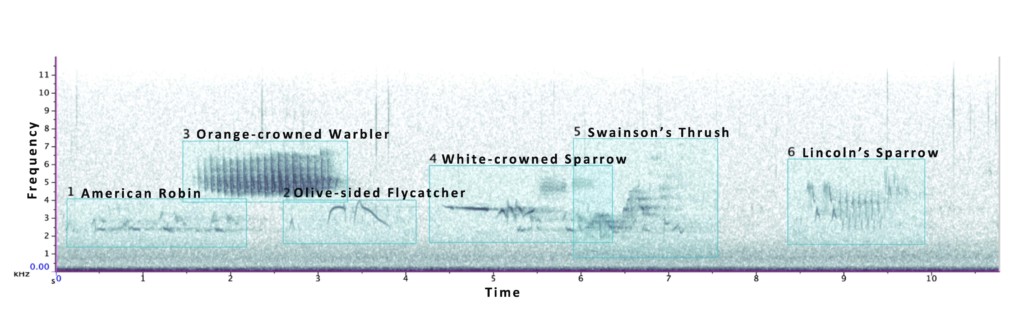

When you visit your favourite National Park, there are two sounds you are almost guaranteed to hear: birds and aircraft. I didn’t pay close attention to the sounds around me until I became an acoustic analyst at the Colorado State University Listening Lab. My job was to identify the natural and non-natural sounds present in National Parks with the use of spectrograms, a visual representation of sound over time. While I was meant to simply identify whether birds were present, I became intrigued by the songsters and began to unravel the bird chorus piece by piece. The song of each bird, these ever-present but elusive vagabonds, became distinguishable. It was this lab that opened my ears to the incredible complexity and diversity of the acoustic environment. It was also here where I discovered just how much noise permeates across our protected lands. Aircraft, in particular, are a significant part of the acoustic environment in most National parks (Buxton et al., 2019), and it made me wonder how noise impacts the birds that rely so much on their song to communicate.

When you visit your favourite National Park, there are two sounds you are almost guaranteed to hear: birds and aircraft. I didn’t pay close attention to the sounds around me until I became an acoustic analyst at the Colorado State University Listening Lab. My job was to identify the natural and non-natural sounds present in National Parks with the use of spectrograms, a visual representation of sound over time. While I was meant to simply identify whether birds were present, I became intrigued by the songsters and began to unravel the bird chorus piece by piece. The song of each bird, these ever-present but elusive vagabonds, became distinguishable. It was this lab that opened my ears to the incredible complexity and diversity of the acoustic environment. It was also here where I discovered just how much noise permeates across our protected lands. Aircraft, in particular, are a significant part of the acoustic environment in most National parks (Buxton et al., 2019), and it made me wonder how noise impacts the birds that rely so much on their song to communicate.

Figure 1 An example of a spectrogram with boxes around individual species’ vocalizations. Higher-pitched sounds are reflected by higher frequencies and louder sounds are darker in colour.

Figure 1 An example of a spectrogram with boxes around individual species’ vocalizations. Higher-pitched sounds are reflected by higher frequencies and louder sounds are darker in colour.

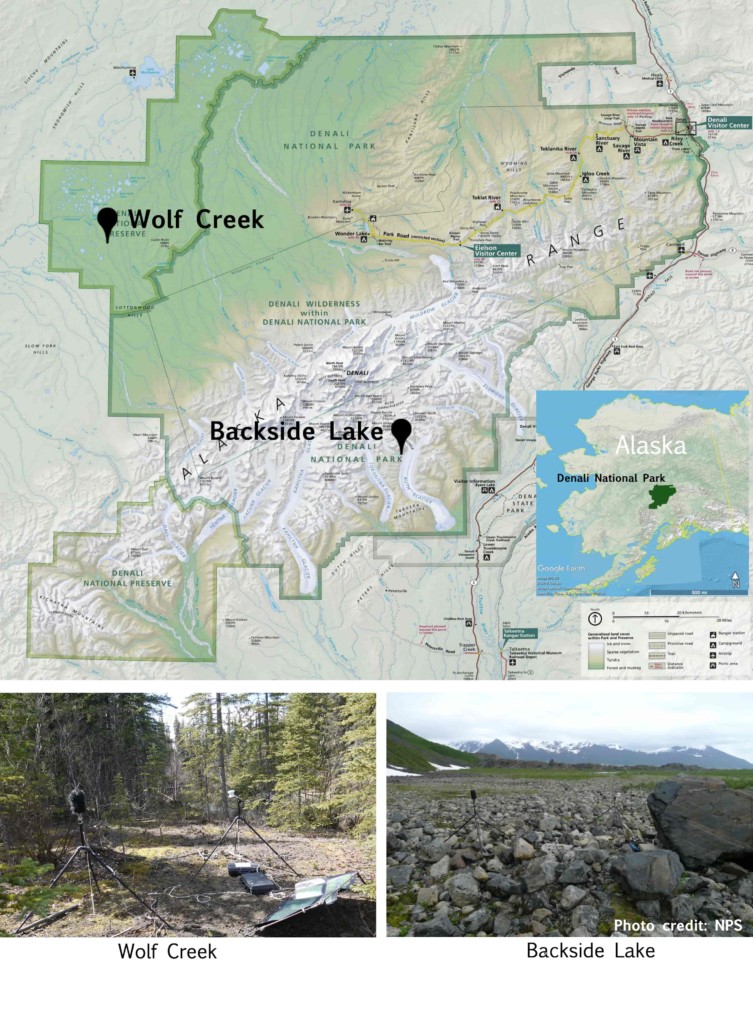

We formed a team to unpack this question with a massive dataset collected over decades by the park service: over 3000 hours of recordings analysed by technicians like myself from National Parks all over the country. We then focused on two remote locations in Denali National Park with a rich diversity of singing birds. These sites had different levels of aircraft noise, with one site being much noisier than the other. We observed how the number of singing bird species changed in response to the sound of aircraft. Over the course of a few months, I unveiled the constituents of these two Denali bird communities. I came to know the rhythms of their songsters better than almost anywhere I had been before. The spectrograms painted a picture of the landscape and embodied the birds as much as any photograph. It gave me a glimpse into the world of birds without humans around.

Figure 2 A map of the selected sites in Denali National Park. Wolf Creek is the lower elevation, riparian back country site with less exposure to aircraft noise. Backside Lake is the higher elevation, relatively exposed front country site with more exposure to aircraft noise.

Figure 2 A map of the selected sites in Denali National Park. Wolf Creek is the lower elevation, riparian back country site with less exposure to aircraft noise. Backside Lake is the higher elevation, relatively exposed front country site with more exposure to aircraft noise.

When we analysed the results, what we found was unexpected — at the quieter site, the number of different bird species singing and calling was higher after the sound of a passing aircraft. Yet, at the noisier site there was no difference in the number of bird species heard. It seemed that the community of birds at the quieter site were more responsive to aircraft. The acoustic environment is complex and dynamic, making it difficult to understand direct cause-effect relationships. However, one thing became clear: aircraft noise particularly affects birds in quiet places. In a world that is becoming increasingly noisy, this has important implications for conserving wild places.

In visualizing sounds I not only discovered a wonderful pastime in birding but also learned to appreciate sound as an invaluable component of ecosystems. Birds are one of the many voices that can help us better understand our world. They not only stimulate our curiosity for nature but also provide an early warning to ecological disharmony. All we need to do is listen.

References

Buxton, R.T., McKenna, M.F., Mennitt, D., Brown, E., Fristrup, K., Crooks, K.R., Angeloni, L.M. & Wittemyer, G. 2019. Anthropogenic noise in US national parks – sources and spatial extent. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 17(10): 559–564. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Airplane approaching Mt. McKinley on a perfect summer afternoon. Denali National Park and Preserve, U.S. National Park Service.