LINKED PAPER  Using satellite tracking to assess the use of protected areas and alternative roosts by Whooper and Bewick’s Swans. Wilson, J.C., Wood, K.A., Griffin, L.R., Brides, K., Rees, E.C., Ezard, T.H.G. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13369. VIEW

Using satellite tracking to assess the use of protected areas and alternative roosts by Whooper and Bewick’s Swans. Wilson, J.C., Wood, K.A., Griffin, L.R., Brides, K., Rees, E.C., Ezard, T.H.G. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13369. VIEW

Bewick’s and Whooper Swans are two migratory species which overwinter in the UK, and many of the sites where they reside are designated as protected areas to conserve these species. In the UK, wintering Bewick’s Swan numbers are declining because of reducing apparent breeding success and range shifts associated with climate change. Meanwhile, Whooper Swan wintering numbers are growing rapidly as survival rates improve and their wintering range expands. Both species typically roost in shallow water at wetlands, but observations have been made of swans using alternative roost sites instead, such as irrigation reservoirs. Here, swans will not receive the benefits provided by reserves, such as protection from predators or disturbance. In our efforts to protect these species, it is important to understand how often they leave protected areas to roost and why they do so.

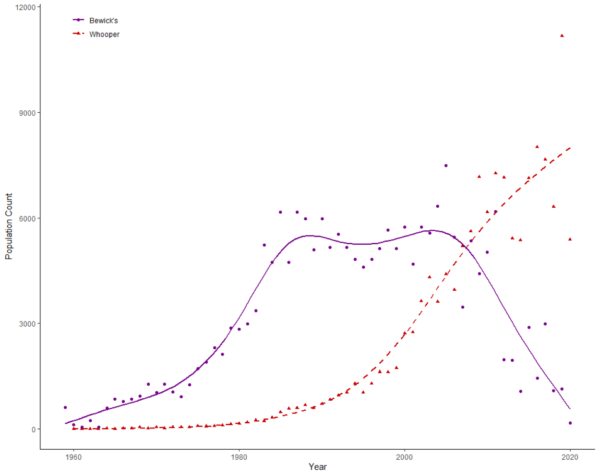

The Ouse Washes in southeast England host over 1% of the flyway populations of Northwest European Bewick’s Swans (Beekman et al. 2019) and Icelandic Whooper Swans (Brides et al. 2021). This wintering site is therefore protected, with reserves that are managed by the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Population trends of swans here reflect the species as whole, with recent declines seen for Bewick’s Swans and increases seen for Whooper Swans (Fig. 1) The surrounding land is mainly farmland, where swans consume post-harvest remains of crops during the day, before returning to reserves at dusk to roost. The Ouse Washes also serve as floodwater conveyance channels, meaning that water is diverted into the wetland during periods of peak river flow and spring tides to protect nearby farmland and properties. Previous observations here have noted that flooding and freezing both limit access to shallow water, leading to dispersal of roosting swans to locations outside of reserves (Scott 1980; Bowler et al. 1994).

Figure 1. Counts of Bewick’s and Whooper Swans at the Ouse Washes from 1959 to 2020. Trend lines produced with a generalised additive model. Contains Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) data from Waterbirds in the UK 2019/20 © copyright and database right 2021. WeBS is a partnership jointly funded by the BTO, RSPB and JNCC with fieldwork conducted by volunteers.

We tagged 18 Bewick’s Swans and 15 Whooper Swans to understand roosting behaviour inside and outside of protected areas. We looked at nighttime behaviour of swans to investigate how often swans roosted within protected areas, and where else they often roosted instead. We also used river level and temperature data to assess how flooding and freezing might influence roosting and foraging behaviour.

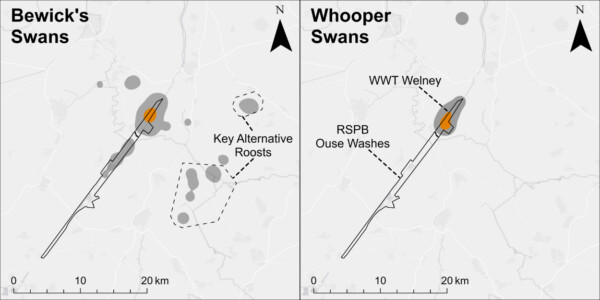

Bewick’s Swans roosted outside of protected areas 23.7% of the time overall. This varied between individual swans, with one individual only leaving on 6.7% of nights, and another not roosting within a protected area once. Swans that were tagged for multiple years changed their behaviour year to year, with one roosting outside of protected areas 4% of the time one year and 60.1% of the time the next. Whooper Swans, meanwhile, only roosted outside of protected areas on 4.5% of nights overall, though this may be an underestimate as swans were not tagged in the middle of winter, when Bewick’s Swans were most likely to leave protected areas. Most of the alternative roost sites were located at a nearby network of irrigation reservoirs, or on the banks of the River Little Ouse or River Wissey (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Roost distributions for Bewick’s Swans (left) and Whooper Swans (right) that primarily roost at WWT Welney, a reserve in the Ouse Washes. The most used areas are highlighted in orange while other often-used areas are highlighted in light grey. Protected areas are outlined with a solid black line, while key alternative roost sites home to resident swans are outlined with a dashed black line.

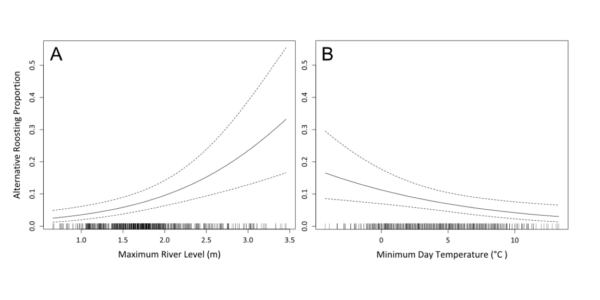

Bewick’s Swans were also more likely to roost elsewhere during periods of flooding and freezing. The predicted propensity for alternative roosting rose from 3% at the lowest river levels to 34% at the highest river levels (Fig. 3a). Similarly, at the lowest observed temperatures, swans were predicted to roost outside of protected areas 17% of the time, compared with just 3% during the warmest periods (Fig. 3b). This could be because both flooding and freezing cause a decline in the availability of shallow water at reserves, whereas irrigation reservoirs and rivers still offer roost habitat during these times. However, there could be other factors at play.

Figure 3. The predicted proportion of nights spent at alternative roosts among Bewick’s Swans from WWT Welney in relation to environmental conditions. The rug plot along the bottom of each panel indicates where along the x-axis measurements were recorded.

Foraging behaviour also impacts roosting behaviour, as swans seek to save energy by roosting elsewhere to minimise the distance they must fly to reach their feeding sites. Among swans that remained at protected areas, foraging flight distances also varied with flooding. The predicted distance rose from 3.5km during the lowest river levels to 6km at the highest levels, probably because nearby low-elevation farmland was also affected. This means that swans must use more energy to feed during periods of flooding if they continue roosting within reserves. However, if they use alternative roost sites, they can reduce these flight distances by approximately 2km during periods where river level was highest.

So swans do not always use protected areas, despite the many benefits they offer. Both flooding and freezing cause swans to use alternative roosts more often, by limiting roost availability and increasing the distance that swans must fly to forage. With increased flooding expected in the UK due to climate change (Kendon et al. 2020), swans might be forced to roost outside protected areas more often, limiting the effectiveness of conservation efforts. As swan species exhibit range shifts and changes to population sizes, it would be beneficial to look at other reserves to inform new protection measures.

References

Beekman, J., Koffijberg, K., Wahl, J., Kowallik, C., Hall, C., Devos, K., Clausen, P., Hornman, M., Laubek, B., Luigujõe, L. (2019) Long-term population trends and shifts in distribution of Bewick’s swans Cygnus columbianus bewickii wintering in northwest Europe. Wildfowl 5:73-102. VIEW

Bowler, J.M., Butler, L., Liggett, C., Rees, E.C. (1994) Bewick’s and Whooper Swans Cygnus columbianus bewickii and C. cygnus: the 1993-94 season. Wildfowl 45:269-275. VIEW

Brides, K., Wood, K.A., Hall, C., Burke, B., McElwaine, G., Einarsson, O., Rees, E.C. (2021) The Icelandic Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus population: current status and long-term (1986–2020) trends in its numbers and distribution. Wildfowl 71:29-57. VIEW

Kendon, E.J., Roberts, N.M., Fosser, G., Martin, G.M., Lock, A.P., Murphy, J.M., Senior, C.A., Tucker, S.O. (2020) Greater Future U.K. Winter Precipitation Increase in New Convection-Permitting Scenarios. Journal of Climate 33:7303-7318. VIEW

Scott, D.K. (1980) The behaviour of Bewick’s swans at the Welney Wildfowl Refuge, Norfolk, and on the surrounding fens: a comparison. Wildfowl 31:5-18. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Resting Bewick’s Swan at WWT Slimbridge in Gloucestershire, UK © Mark Dowie (@MarkDowie).