It’s a chilly spring evening in southeastern Sweden and I am driving with Björn Westman to one of his study sites. Björn was an outstanding naturalist working on his PhD at Uppsala University on Great Tits but our destination was one of his side projects. I was visiting the university for a few months during my first sabbatical year, keen to see all the bird species that the students there were working on.

On arriving at Björn’s study area well after dark, we hiked maybe a hundred metres into the woods to spend the night in Björn’s hide on the edge of a large bog. We slept fitfully, drank some of Björn’s homemade brännvin to keep warm, and argued about the mechanisms of sexual selection.

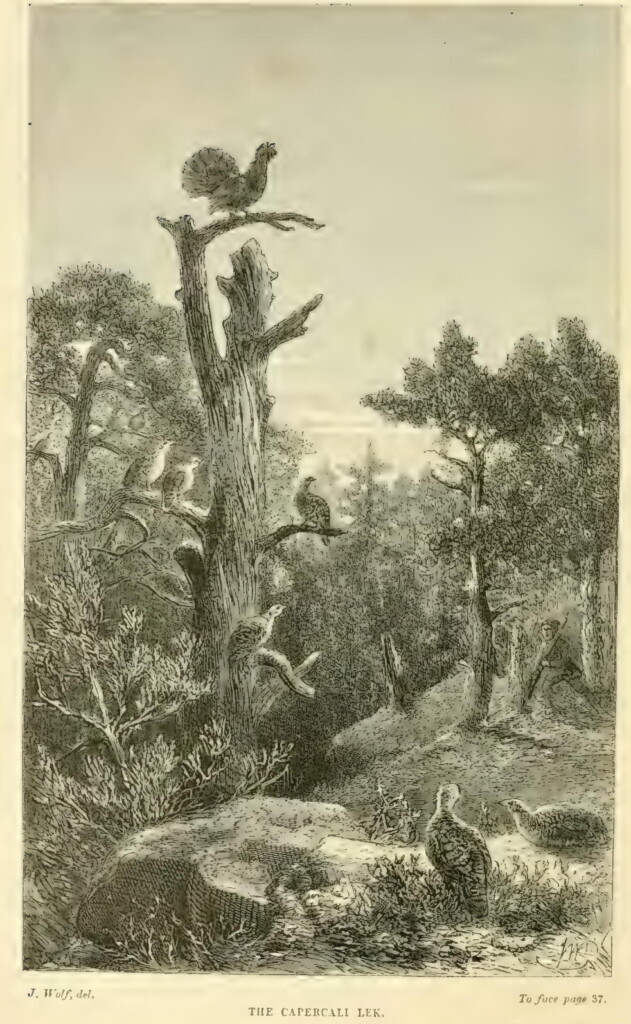

We were both jolted awake by what sounded like a gun shot. Björn grabbed my arm and growled ‘They’re here!” I peered out a slit in the hide and there, not two metres away, was a steam-breathing dinosaur—Capercaillie!—standing in the mist rising from the bog. The bird seemed impossibly large and menacing. He turned to give us a stink-eye before going about his business strutting around and uttering a long series of growls, cackles, and those startling gunshots (video here). A female soon fluttered down from the trees and all hell broke loose as two more males began to court and spark. As so often happens at a lek, the female seemed to ignore the males as she foraged on the ground, then quietly left while the males continued to strut. Within an hour the sun was up and the birds faded back into the forest.

‘Capercaillie’ is one of those wonderful old English bird names that are a single word—Dunlin, Whimbrel, Dotterel—that give them celebrity status in my mind, like Prince, Bono, Beyoncé and Shakira. The OED says that the word ‘capercaillie’ first appeared in print in John Bellenden’s (1536) book translating Hector Boece’s Latin text Historia Gentis Scotorum [History of the Scottish People] published in 1527: “Many other birds are in Scotland, which are seen in no other parts of the world; as capercaillie, a bird bigger than a raven, which lives only on tree-bark.” [Here in a modern translation of Bellenden’s original Scots]. During the subsequent 500 years, the species’ name has been variously rendered as ‘Capercailzie’, ‘Caperkyley’, ‘Caper coille’, ‘Caper Keily’, ‘Caperkelly’, and ‘cobberkely’ (Grant 1929-46).

All those variants on the name ‘Capercaillie’ derive from the original Gaelic ‘capal-coille’ —Horse of the Woodland—from ‘capull’ meaning horse (from the Latin ‘caballus’) and ‘coille’ meaning forest or wood. The great 19th century naturalist, William Yarrell [1784-1856], believed that the bird was called ‘horse’ because of its size: “…this species being in comparison with others of the genus pre-eminently large, this distinction is intended to refer to size, as it is usual now to say horse-mackerel, horse-ant, horse-fly, horse-leach, and horse-radish.” I think he was (uncharacteristically) mistaken as horse-flies are often found around horses; the horse-mackerel is an anglicized version of the Dutch ‘Horsmakreel’—the mackerel that spawns in shallow waters (‘hors’ in Dutch); horse leeches often attach to horses; and the word ‘horseradish’ is probably a mispronunciation of the German name ‘meerrettich’ or ‘sea radish’ where ‘meer’ in German sounds like ‘mare’. It seems more likely to me that the Capercaillie is named for its vocalizatons that resemble the clip-clop of a horse walking along a hard road. This is the gun-report-like ‘Kikop’ call (de Juana & Kirwan 2020) that woke us up at Björn’s Capercaillie lek on that misty spring morning, audible from at least 300 m away in the woods and downright startling at 2 metres.

Although once common throughout the British Isles, the Western Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) was probably extinct in England and Wales by the 1300s, by 1760 in Ireland, and by 1785 in Scotland (Stevenson 2007). It was clearly a “victim of being a large and obvious game bird in a dwindling natural environment full of hungry people” (Cramp & Simmons 1980: 434), as the ancient pine forests were cleared and the human population burgeoned. Then in the 1830s, John Campbell, the 2nd Marquess of Breadalbane [1796-1862], and Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton [1786-1845] hatched a plan to reintroduce the Capercaillie to Scotland. To do that, they obtained more than 40 young-of-the-year Capercaillie from Buxton’s cousin, Llewellyn Lloyd, who I introduced on this blog last month (here). Lloyd captured the birds in Sweden where he lived and gave them to Buxton’s gamekeeper, Larry Banville, to take by sea back to Scotland. Campbell’s estate, the seat of the Campbell clan, comprised 180 ha of woodland, fields, and Taymouth Castle, in the heart of the Grampian Mountains. Campbell’s head gamekeeper, James Guthrie, then raised the birds on the estate, and released 29 females and 13 males there the following spring. Within 25 years there were 1000-2000 descendants of those birds on Campbell’s estate. By the 1970s that population had grown to at least 20,000 birds scattered across various locations throughout Scotland. Several other attempts to reintroduce Swedish Capercaillie to England and Scotland over the next two centuries had failed.

While this appears to be an amazingly successful reintroduction of a charismatic bird, the Capercaillie population in Scotland has crashed during the past 50 years to number only about 500 today. This time the culprit is probably climate change and the Scottish population of Capercaillie seems likely to be doomed once again.

Further Reading

Cramp, S. & Simmons, K. E. L. (1980) The birds of the Western Palearctic. Volume II., pp. 695. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Juana, E. and G. M. Kirwan (2020). Western Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Goodenough, A.E. & Webb, J.C. (2025) Pollen analysis as a tool to advance avian research and inform conservation strategies. Ibis VIEW

Grant, W., editor (1929-46) The Scottish National Dictionary. Designed partly on regional lines and partly on historical principles, and containing all the Scottish words known to be in use or to have been in use since c. 1700. Edinburgh: The Scottish National Dictionary Association Ltd< VIEW

Lloyd, L. 1867. The game birds and wild fowl of Sweden and Norway; with an account of the seals and salt-water fishes of those countries. London: F. Warne and co. VIEW

Stevenson, G.B. (2007) An historical account of the social and ecological causes of capercaillie Tetrao urogallus extinction and reintroduction in Scotland. PhD thesis, University of Stirling. VIEW

Image credits

Capercaillie head, photo by Simon Bailey, 22 March 2013, Wikimedia, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Capercaillie leks from Lloyd (1867); engraving from painting by Magnus Körner and woodcut by Joseph Wolf