A REPORT FROM A BOU-FUNDED CAREER DEVELOPMENT BURSARY

The author was awarded a bursary of £2,500 in 2019 to undertake this project

In 2019, I was the fortunate recipient of a BOU Career Development Bursary. This scheme aims to develops the skills of researchers early in their careers by funding short-term research positions in a third-party institute, where they are mentored by a supervisor/sponsor. Here I describe my experience, including data collection, analysis and the collaborations that transpired from my award.

My work with seabirds began in 2017 with a brief email to Dr. Jacob Gonzalez-Solis, a world-renowned researcher from Barcelona who has been working with Cabo Verde seabirds since 2004. I had just finished my Masters in Canada, and serendipitously ended up in Cabo Verde with no direction in sight. The email itself was rather naïve, a few lines saying that I was in Cabo Verde, available and extremely keen to work with seabirds. Little did I know that this would be the start of two years of data collection on the nation’s highest peaks and most remote islets searching for seabirds.

It all started on the large but uninhabited islet of Raso, a moon-like place of volcanic outcrops with little vegetation, strong winds, and rough seas – in other words a paradise for seabirds. Here I was introduced to the Red-billed Tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus), a little-known species that inhabits tropical oceans around the world. With its predominantly white body, long tail streamers, red bill and black mask, locals often consider it the country’s most beautiful bird. Our work consisted of monitoring, sampling and tracking birds with GPS and geolocators. With species that spend so little time on land and so much at sea, tracking studies are indispensable for understanding the where, when and why of animal movements. This information is crucial for the development of effective spatial conservation measures, such as marine protected areas, and is almost completely lacking in tropical systems.

After several months of eating rice and beans in Raso, I was happy to return to inhabited islands. Here, my work with tropicbirds continued and I started working with local NGOs such as Projecto Vitó, Project Biodiversity and BIOS.CV to track tropicbirds breeding on the islands of Sal and Boavista and, eventually, Cima islet in a large project on Cabo Verde seabirds that is coordinated by Birdlife International and funded by the MAVA Foundation. Over the next two years, I helped coordinate over 25 volunteers and research technicians in an effort to monitor hundreds of breeding tropicbirds, tracking ≈1000 foraging trips with GPS and 45 year-round movements with geolocators! This effort was coupled with conservation and public awareness campaigns to reduce threats on land such as predation by dogs, rats and cats, and human harvest for meat.

Figure 1 Red-billed Tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus) chick © Marcos Hernández-Montero

I became more and more invested in the results of the study and started to speak to Jacob about working with the data I had collected. In 2018, I returned for a second field campaign in Raso, this time joined by Dr. Sam Cox, a CNES-funded research fellow at the UMR-MARBEC of the IRD in Sète, France who is working on the foraging ecology of boobies, another tropical genus. With a similar question in mind, Sam came to Raso to participate in the collection of GPS tracks from the islets’s colony of Brown Boobies (Sula leucogaster). Following this field campaign, we decided to apply together for the BOU Career Development Bursary to analyze tropicbird data with some of the approaches she used for boobies. We received the bursary and in April 2019, I travelled to Sète to work with Sam on the foraging ecology of tropicbirds.

Figure 2 Field Camp in Raso 2018 © Sam Cox

During this BOU Career Development Bursary project, we investigated the foraging ecology of 251 GPS-tracked Red-billed Tropicbirds during the breeding period. I first split GPS deployments into 529 discrete foraging trips, and categorised each position into behavioural states with a Hidden Markov Model (HMM). HMMs are an advanced statistical approach in which observed time-series data (such as GPS tracks of movement) are connected to different behavioural states. For seabirds, these states may correspond to periods of resting, foraging or travelling (Fig. 3). These results enabled us to select only foraging positions to define core foraging areas and to compare these areas between islands, colonies, season and breeding stages. We also incorporated oceanographic features into the HMMs to determine whether the likelihood of transitions from one state to another were related to fronts and eddy edges (which are indicative of convergence zones that may enhance prey availability).

Figure 3 Red-billed Tropicbird foraging trip with Hidden Markov Model behavioural classifications (blue = travelling, red = foraging and orange = resting)

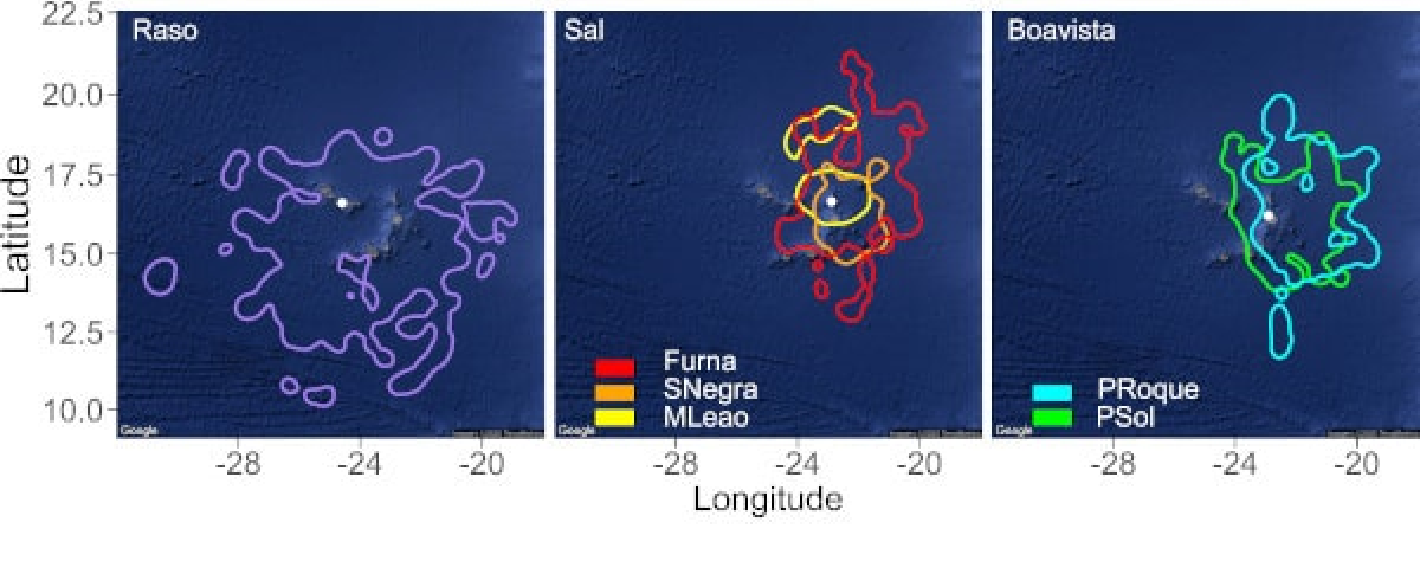

We found that tropicbirds foraged in oceanic waters as much as 720 km from their colonies. Core foraging areas of all colonies overlapped, although this overlap was greatest between colonies of the nearby easterly islands of Sal and Boavista. The birds nesting in the westerly island of Raso overlapped less with the other colonies and had larger and more circular core foraging areas, showing that individuals from this islet may need to travel greater distances to find food. We found little association between tropicbird foraging behaviour and the proximity to fronts and eddies, suggesting that foraging areas cannot be predicted based on environmental variables alone. Our results provide some of the first in-depth knowledge on the foraging ecology of Red-billed Tropicbirds and underline how substantial colony-level differences and low environmental predictability can challenge the effective conservation management of tropical seabirds.

Figure 4 Core foraging areas of Red-billed Tropicbirds breeding on three islands in Cabo Verde. Colours represent different colonies

My experience with the bursary has been extremely positive. I learnt much about analysing tracking data and how to model the relationships between seabird behaviour and oceanographic variables. Many of the specific analytical skills learnt, such as the processing and analysis of GPS data with Hidden Markov Models, are transferable to the PhD I started in July 2019 on tropicbird foraging and migratory ecology around the world. Also, the collaborations that took root during this bursary have continued to develop since my stay in Sète and will play a critical role in the success of my PhD.

Figure 5 Group photo, Raso 2018 © Sam Cox

This work was presented at Congreso VII Iberico XXIV Español de Ornitología and we submitted an abstract for an oral presentation at the World Seabird Conference.

I am very grateful to the BOU for awarding me this Career Development Bursary.

Figure 1 Red-billed Tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus) chick © Marcos Hernández-Montero

I became more and more invested in the results of the study and started to speak to Jacob about working with the data I had collected. In 2018, I returned for a second field campaign in Raso, this time joined by Dr. Sam Cox, a CNES-funded research fellow at the UMR-MARBEC of the IRD in Sète, France who is working on the foraging ecology of boobies, another tropical genus. With a similar question in mind, Sam came to Raso to participate in the collection of GPS tracks from the islets’s colony of Brown Boobies (Sula leucogaster). Following this field campaign, we decided to apply together for the BOU Career Development Bursary to analyze tropicbird data with some of the approaches she used for boobies. We received the bursary and in April 2019, I travelled to Sète to work with Sam on the foraging ecology of tropicbirds.

Figure 2 Field Camp in Raso 2018 © Sam Cox

During this BOU Career Development Bursary project, we investigated the foraging ecology of 251 GPS-tracked Red-billed Tropicbirds during the breeding period. I first split GPS deployments into 529 discrete foraging trips, and categorised each position into behavioural states with a Hidden Markov Model (HMM). HMMs are an advanced statistical approach in which observed time-series data (such as GPS tracks of movement) are connected to different behavioural states. For seabirds, these states may correspond to periods of resting, foraging or travelling (Fig. 3). These results enabled us to select only foraging positions to define core foraging areas and to compare these areas between islands, colonies, season and breeding stages. We also incorporated oceanographic features into the HMMs to determine whether the likelihood of transitions from one state to another were related to fronts and eddy edges (which are indicative of convergence zones that may enhance prey availability).

Figure 3 Field Camp in Raso 2018 © Sam Cox

We found that tropicbirds foraged in oceanic waters as much as 720 km from their colonies. Core foraging areas of all colonies overlapped, although this overlap was greatest between colonies of the nearby easterly islands of Sal and Boavista. The birds nesting in the westerly island of Raso overlapped less with the other colonies and had larger and more circular core foraging areas, showing that individuals from this islet may need to travel greater distances to find food. We found little association between tropicbird foraging behaviour and the proximity to fronts and eddies, suggesting that foraging areas cannot be predicted based on environmental variables alone. Our results provide some of the first in-depth knowledge on the foraging ecology of Red-billed Tropicbirds and underline how substantial colony-level differences and low environmental predictability can challenge the effective conservation management of tropical seabirds.

Figure 4 Core foraging areas of Red-billed Tropicbirds breeding on three islands in Cabo Verde. Colours represent different colonies

My experience with the bursary has been extremely positive. I learnt much about analysing tracking data and how to model the relationships between seabird behaviour and oceanographic variables. Many of the specific analytical skills learnt, such as the processing and analysis of GPS data with Hidden Markov Models, are transferable to the PhD I started in July 2019 on tropicbird foraging and migratory ecology around the world. Also, the collaborations that took root during this bursary have continued to develop since my stay in Sète and will play a critical role in the success of my PhD.

Figure 5 Group photo, Raso 2018 © Sam Cox

This work was presented at Congreso VII Iberico XXIV Español de Ornitología and we submitted an abstract for an oral presentation at the World Seabird Conference.

I am very grateful to the BOU for awarding me this Career Development Bursary.