Report from a BOU-funded project

Communal roosting, the gathering of more than two individuals resting together, is a common behaviour in animals, especially birds. Such behaviour can provide several benefits: greater safety from predators, reduced thermoregulation costs, and the chance to share information about patchily distributed food sources (Ward & Zahavi, 1972; Bijleveld et al., 2010). Roosts are also useful for studying population dynamics. By monitoring them, researchers can estimate the number of individuals in an area and identify ecological or environmental factors that favour their establishment (Hill et al., 2021). When communal roosts are located in urban ecosystems, they bring birds and people into closer contact. This can lead to both positive and negative interactions, particularly when hundreds or even thousands of individuals gather together. With this in mind, we asked: where are the main areas of concentration of Chimango Caracaras (Milvago chimango; hereafter “chimangos”)?

The chimango is a Neotropical falcon with a wide distribution in southern South America, from southern Bolivia to Tierra del Fuego, Argentina (Ferguson-Lees & Christie, 2001). Unlike most raptors, its abundance is positively associated with human disturbance (Carrete et al., 2009). Opportunistic and highly adaptable, it exploits food from agriculture, fishing, garbage dumps, and recreational areas (Biondi et al., 2005; Biondi, 2021).

In communal roosts, chimangos can access information about unpredictable food sources, such as carrion or waste. This increases the chances of interaction with people, sometimes beneficial (carcass removal) and sometimes problematic (feces accumulation, garbage scattering). Our study therefore aimed to identify where these birds congregate, what environmental factors shape their roosts, and how they move daily within the urban matrix, with the broader goal of informing management strategies for human–chimango coexistence.

To complement this, we also interviewed residents living near roosting sites to understand local perceptions, whether chimangos are viewed as a nuisance or a welcome neighbour.

Where do chimangos roost?

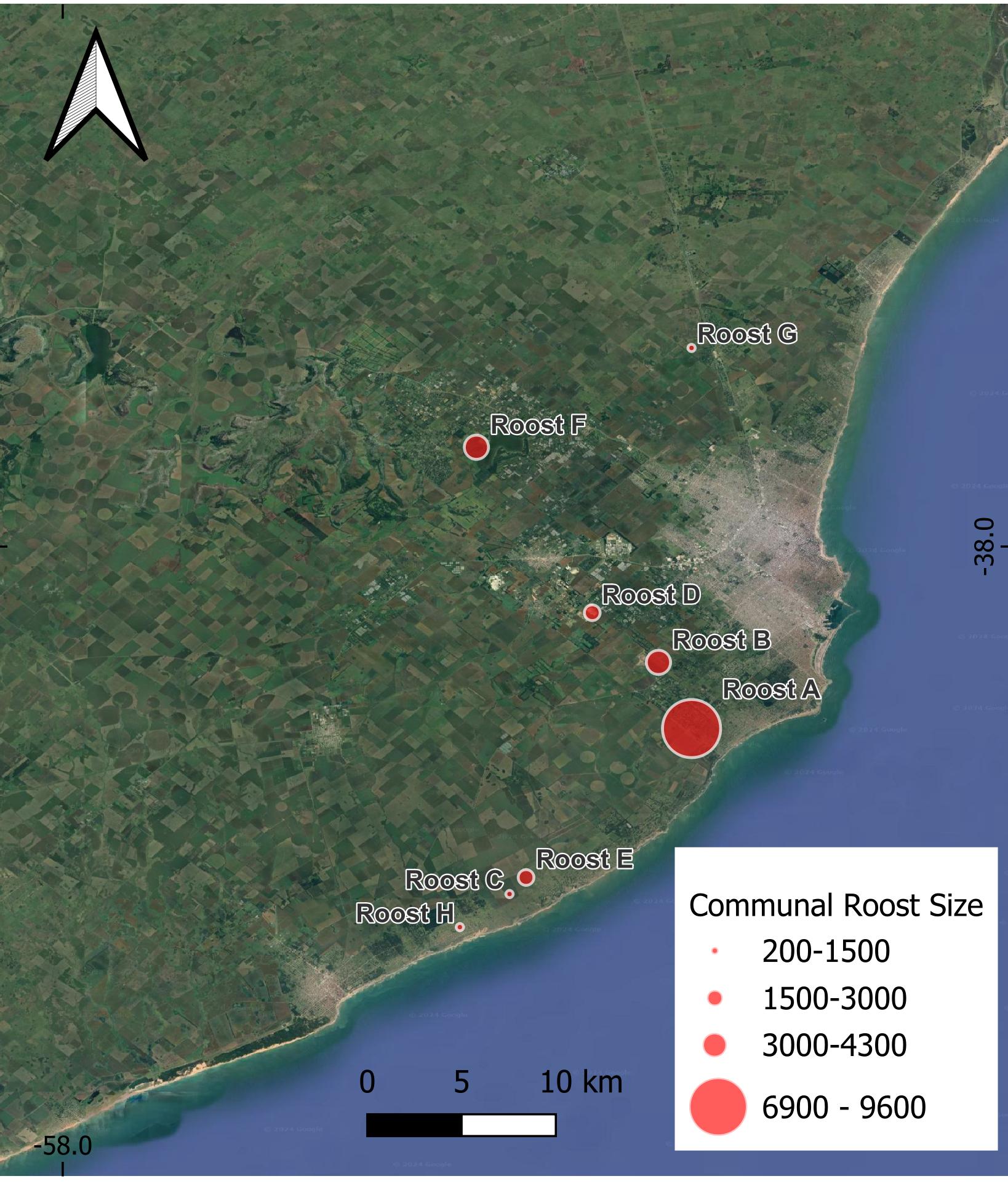

Between 2023 and 2024, we carried out evening counts at eight communal roosts in peri-urban and rural areas of Mar del Plata, Argentina (Figure 1). The chosen sites were diverse: 43% herbaceous vegetation or shrubs, 23% fields, and 18% trees (Figure 2). This diversity highlights once again the species’ecological plasticity.

Figure 1. Distribution of communal roosts of Chimango Caracaras in the study area. Circle size represents the number of individuals attending each roost.

Figure 1. Distribution of communal roosts of Chimango Caracaras in the study area. Circle size represents the number of individuals attending each roost.

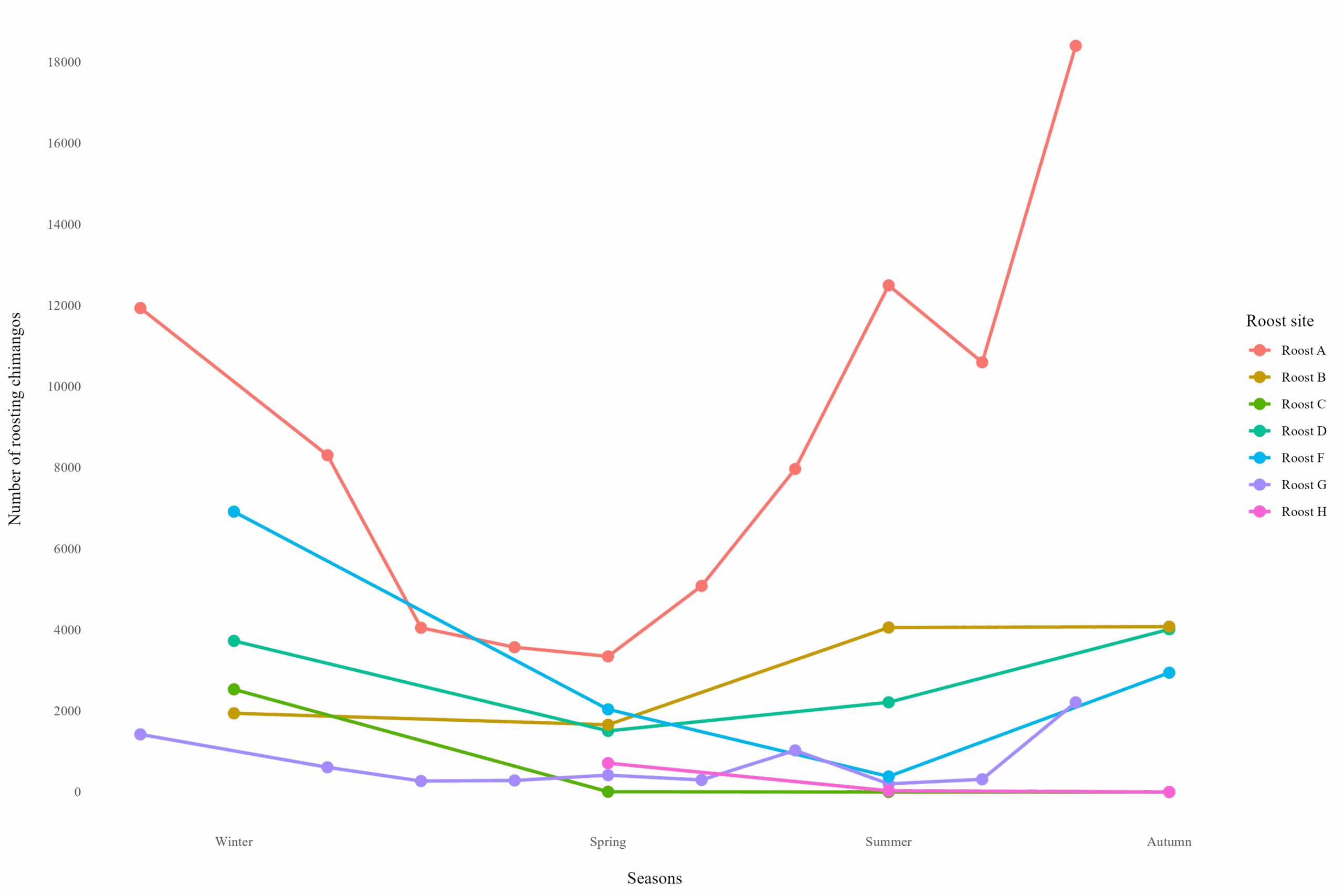

Roost size varied greatly, ranging from 100 to 18400 individuals (mean: 3,593 ± 659 SE) (Figure 3). The largest roost was located in a neighborhood on the outskirts of the city. Peak arrivals occurred just after sunset, with an average of 1138 individuals entering per evening.

Figure 2. Communal roost of chimangos caracara monitored in the study.

Figure 2. Communal roost of chimangos caracara monitored in the study.

Figure 3. Number of roosting chimangos across seasons for each roost site.

Figure 3. Number of roosting chimangos across seasons for each roost site.

Seasonal differences were also evident. Numbers were lowest in spring, coinciding with the breeding season (Figure 3). Some roosts shrank or even disappeared during this period (e.g. Roost F), while others reached their maximum size (e.g. Roosts E and H). These patterns suggest a dynamic system, where chimangos shift between roosts depending on proximity to breeding territories and nesting sites.

Figure 4. Number of roosting chimangos counted in the eight roosts across the seasons.

Figure 4. Number of roosting chimangos counted in the eight roosts across the seasons.

Tracking movements with GPS

So far, our counts have provided valuable information on the size and distribution of communal roosts. But where do chimangos come from, and how far do they travel to sleep? Would an individual from the city choose a nearby square, or fly long distances to join a larger roost?

To answer this, we tested a low-cost GPS on urban chimangos at our university campus (Figure 4). One tracked bird flew 13 km from downtown Mar del Plata to Roost B just before sunset, then returned to campus the next morning. Unfortunately, the device stopped transmitting after that.

Still, this pilot test was promising. Thanks to BOU funding, we are now developing affordable GPS units capable of working for weeks or even a month. These will allow us to investigate whether chimangos are faithful to particular roosts and to better understand their daily movements. Importantly, developing this kind of technology locally is crucial, as commercial devices are often prohibitively expensive elsewhere in the world, and Argentina is currently facing a critical funding situation in science.

Figure 5. Chimango Caracara with GPS attached.

Figure 5. Chimango Caracara with GPS attached.

What do people think?

But what about the people living alongside these massive gatherings? Do they tolerate them? Even notice them?

We interviewed 100 residents near Roost A, the largest site. Most were aware of the huge flocks, and reported that the roost had been established there for an average of eight years (range: 3–20). The main conflict cited was chimangos tearing open garbage bags, a result consistent with our previous nationwide online survey (Bonetti et al., in prep).

Despite this, over half of respondents expressed tolerance toward the birds, even appreciating their presence. Some highlighted pest control as a benefit, while others described the spectacular evening flights before roosting as a cultural ecosystem service.

Funding

In 2024 Eugenia was awared an Brenda and Anthony Gibbs award of £1933.39 for the project title: “Communal roosting behavior of a Neotropical raptor (Milvago chimango) at the city: identifying potential conflicts and benefits for the society and the environment” when she was a PhD Student at the Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras (IIMyC) in Argentina.

References

Bijleveld, A.I., Egas, M., Van Gils, J.A. & Piersma, T. 2010. Beyond the information centre hypothesis: communal roosting for information on food, predators, travel companions and mates? Oikos, 119: 277–285.

Biondi, L.M. & Piersma, T. 2021. Falconiformes Cognition. In: Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior (J. Vonk & T. Shackelford, eds), pp. 1–9. Springer International Publishing, Cham.

Biondi, L.M., Bó, María Susana & Favero, M. 2005. Dieta del Chimango (Milvago chimango) durante el período reproductivo en el Sudeste de la provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina Ornitol. Neotrop., 16.

Carrete, M., Tella, J.L., Blanco, G. & Bertellotti, M. 2009. Effects of habitat degradation on the abundance, richness and diversity of raptors across Neotropical biomes. Biol. Conserv. , 142: 2002–2011.

Ferguson-Lees, J. & Christie, D.A. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hill, J.E., Kellner, K.F., Kluever, B.M., Avery, M.L., Humphrey, J.S., Tillman, E.A., DeVault, T.L. & Belant, J.L. 2021. Landscape transformations produce favorable roosting conditions for turkey vultures and black vultures. Sci. Rep., 11: 14793.

Ward, P. & Zahavi, A. 1972. The importance of certain assemblages of birds as ‘Information-Centers’ for food-finding. Ibis, 115: 517–534.

Image credit

Top right: A Chimango Caracara | Cláudio Dias Timm from Rio Grande do Sul, CC BY-SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons

All other photographs were taken by Eugenia Bonetti.