The RSPB is investigating the impacts of climate change on the breeding success of woodland birds including the declining Pied Flycatcher.

The RSPB is investigating the impacts of climate change on the breeding success of woodland birds including the declining Pied Flycatcher.

The onset of spring is getting earlier. Understanding the effects of this on woodland phenology and on the breeding success of woodland birds is being investigated across northern Europe, including in the UK.

We know that our climate is rapidly changing, whatever its cause might be. One consequence of a changing climate, throughout northern Europe, is that the onset of spring has advanced – spring conditions occur earlier now than it did only a few decades ago. Spring is a very important time for many birds, plants and animals. Deciduous trees and many annual plants need to make the most of the short growing season and a huge variety of insects emerges that eats this new growth. Most birds breed in spring to take advantage of the super abundance of insect food available at this time. So how are they adapting to a changing spring?

It is temperature that is important in determining spring activity of trees and animals. Bud burst in trees is triggered by warmer temperatures. Oak leaves first emerge thin and a pale green colour – and at this time they are very palatable to caterpillars which also respond to the warmer spring temperature and synchronise their hatching to feed on the new leaves. But after a short period, trees start to defend themselves by putting toxins, tannins, into the leaves to deter herbivorous insects from eating all their leaves, making them thicken and darken. At this point caterpillars suddenly become much less abundant, as they themselves respond by entering their next life stage, a pupa. This entire spring process results in caterpillars being available in abundance, but only for a short time – perhaps only a few days.

Most hole-nesting woodland birds, such as Blue and Great Tits and the declining Pied Flycatcher, need to carefully time nesting to make the most of this super abundant prey. Caterpillars are the most important food for these breeding birds. These bird species only nest once a year so they have to time it right if they are to successfully raise young. They need to time egg laying to ensure the chicks are at their biggest and hungriest at the same point in spring that caterpillars are most abundant. Too early, or too late, and there probably will not be enough food to raise all the young.

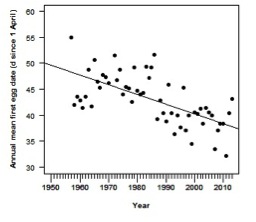

Species need to adapt and respond to a changing climate if they are to persist. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that some species are better able to do this than others. For example, many migratory birds are now arriving back to breeding sites earlier than just a few decades ago. I can see this clearly in my study population of Pied Flycatchers at East Dartmoor in Devon – they arrive earlier and are now laying eggs nearly two weeks earlier than they did in the 1950s (see Figure 1). Another way populations can adapt is by moving to where temperatures do not advance quite as fast or where spring occurs later, such as at higher altitudes or more northern latitudes.

Figure 1. Annual mean first egg date of Pied Flycatchers at East Dartmoor, Devon. This population has been closely monitored since 1955 and provides long term data required to examine effects of changing spring climate on woodland birds

This ecological theory I describe is often simply termed ‘mismatch’, or ‘trophic mismatch’, and is thought to disadvantage migratory birds such as the Pied Flycatcher more than the resident birds like the tits. This might explain why most long distance migratory birds are in such severe decline, in contrast to tits. Resident tits remain around their breeding territories all year so can respond quickly to local cues. Migrants however are not able to predict spring weather in advance from their wintering grounds- so if spring is early they may be less able to arrive earlier. We used to think that Pied Flycatcher departure from Africa was determined by photoperiod, but recent work suggests they can depart earlier (Both 2010). It is likely there is strong evolutionary selection on the timing of migration, as well as on the timing of breeding, which is why we have seen these advances in arrival and breeding in recent decades. But have they advanced sufficiently? One of my jobs is to better understand this theory and see if it really does affect woodland birds in the UK.

Although the mismatch theory is currently popular in evolutionary and conservation science, most of the research is based on work done in the Netherlands. We have little idea if this process occurs in the UK, which is at the extreme western edge of the distribution of many woodland birds including the Pied Flycatcher. One of my roles at the RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, and with the Universities of Exeter and Edinburgh, is to look at mismatch in woodlands across the UK. In his retirement from a career in the RSPB leading on woodland bird conservation science, Ken Smith has been motivating and helping citizen scientists to collect the same data from woodlands across the UK. And now this work links into work at the University of Edinburgh which has a new PhD student, Jack Shutt, who will be undertaking some more ambitious data collection in Scotland.

In my next blog I will describe how we estimate caterpillar abundance and availability, by collecting lots of caterpillar poo… In the meantime, see how you can contribute to this work by recording leaf emergence in your local woodland on the Track a Tree website. By contributing to this you are making a valuable contribution to this wider project.

Reference

Both, C. 2010. Flexibility of timing of avian migration to climate change masked by environmental constraints en route. Current Biology 20: 243-248

Related links

Track a tree – recording spring in woods

Piedfly.net

Image credits

Pied Flycatcher with caterpillar and other insect prey for its young

© Neil Bygrave | www.naturelens.co.uk

Blog with #theBOUblog

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.