LINKED PAPER  Using age-ratios to investigate the status of two Siberian Phylloscopus species in Europe. Dufour, P., Hellström, M. de Franceschi, C., Illa, M., Norevik, G., Cuchot, P., Tillo, S., Bolton, M., Parnaby, D., Penn, A., van der Spek, V., de Knijff, P., VRS Castricum, Damian-Picollet, S., Raitière, W., Lavergne, S., Crochet, P-A., Doniol-Valcroze, P. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13382. VIEW

Using age-ratios to investigate the status of two Siberian Phylloscopus species in Europe. Dufour, P., Hellström, M. de Franceschi, C., Illa, M., Norevik, G., Cuchot, P., Tillo, S., Bolton, M., Parnaby, D., Penn, A., van der Spek, V., de Knijff, P., VRS Castricum, Damian-Picollet, S., Raitière, W., Lavergne, S., Crochet, P-A., Doniol-Valcroze, P. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13382. VIEW

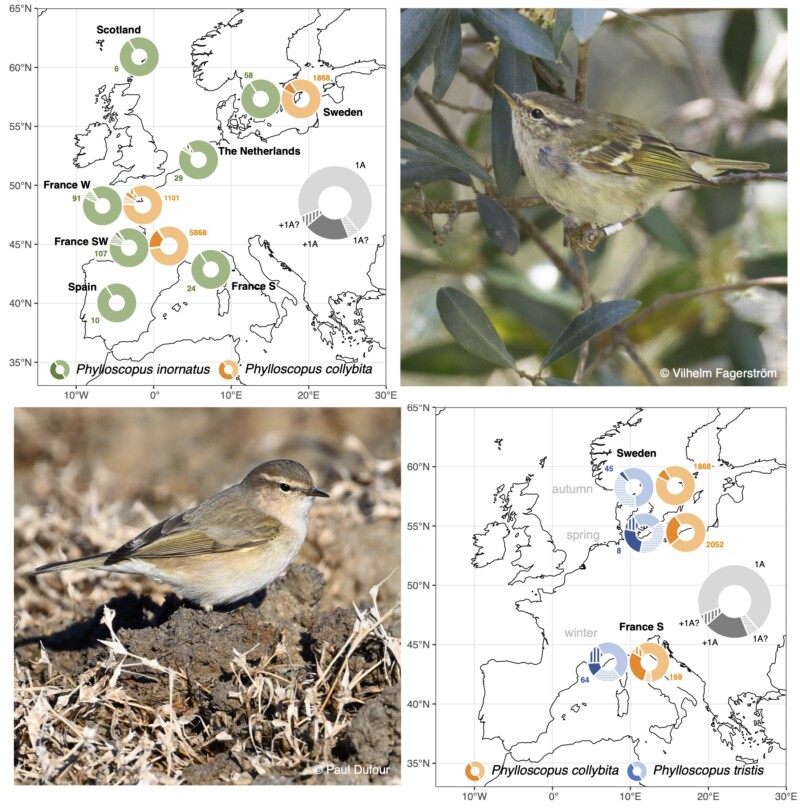

Each autumn, birdwatchers across Europe are thrilled by the unexpected arrival of Siberian species, including the Yellow-browed Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus and the Siberian Chiffchaff Phylloscopus tristis. Their increasing presence in recent decades has sparked questions: are these birds merely lost (i.e., vagrants), or are they using a new and emerging migration route? While hypotheses abound, definitive evidence has remained elusive – until now.

Why study age ratios?

Juvenile migratory songbirds navigate using inherited “maps” that guide their orientation and travel distance. Adults, having survived previous migrations, tend to return along the same routes and use the same orientation throughout their lives. This consistency means that the presence of both young and adult birds in a given area suggests a regular migration route. Conversely, a population dominated by juveniles indicates vagrancy. By comparing age ratios of Yellow-browed Warblers and Siberian Chiffchaffs in western Europe to those of the Common Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita, a seasonal migrant with similar ecology, we sought to unravel their status far from their usual distributions.

Yellow-browed Warbler: an enigma

We used recently-gained expertise on the ageing of this species to estimate age-ratio from photographs of >320 Yellow-browed Warblers captured in Europe. We found that nearly all birds were juveniles (only 1 confirmed and 5 probable adults). This striking result supports the idea that most, if not all, of these birds are vagrants, likely following an erroneous direction at the start of their first migration. The scarcity of adult birds and of spring sightings suggest that few survive the winter or return to Europe in subsequent years. Rare cases of returning individuals, like one in Spain in 2019, are still consistent with the hypothesis of large-scale vagrancy rather than migration. Indeed, this inter-annual control remains unique despite hundreds of individuals being ringed each autumn in Europe, and because we do not know if such individuals manage to return to their breeding grounds to reproduce.

Siberian Chiffchaff: a regular migrant?

In contrast, Siberian Chiffchaffs tell a different story. With 9.4% of adults during migration and nearly 30% of adults in wintering populations in southern France, the data point to a regular migration route distinct from their traditional southward path to the Indian subcontinent. Observations of returning individuals in consecutive winters in southern Europe further bolster the hypothesis of an established westward migration route to Europe.

Figure 1. Age-ratio of Yellow-browed Warblers (green), Siberian Chiffchaffs (blue) and Common Chiffchaffs (orange) caught in Europe. The upper photo shows a Yellow-browed Warbler caught and ringed in Portugal; the bird spent the winter there and moulted some coverts and body feathers in April (photo Vihelm Fagerström). The lower photo shows a Siberian Chiffchaff wintering near Montpellier, France © Paul Dufour.

What these findings mean

These results highlight the complexity of bird migration. For the Yellow-browed Warbler, the data confirm large-scale vagrancy, which constitutes an intriguing evolutionary paradox, as we still do not understand why tens of thousands of individuals fly every autumn towards a near-certain death. Future research will try to unravel the proximate mechanisms behind these large-scale misorientation patterns.

For the Siberian Chiffchaff, our results suggest that the occurrence of the species in Europe involves seasonal migration, although vagrancy might also contribute of course. Further research is needed to investigate if this newly discovered route recently evolved or whether it has been used for some time before it was detected. Identifying the breeding sites of these birds appears as the next step to investigate the evolution and maintenance of this orientation.

References

Dufour, P., Lees, A.C., Gilroy, J., Crochet, P.A. (2024). The overlooked importance of vagrancy in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 39:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2023.10.001

Dufour, P., Åkesson, A., Hellström, M., Hewson, C., Lagerveld, S., Mitchell, L., Chernetsov, N., Crochet, P.A., Schmaljohann, H. (2022). The Yellow-browed Warbler (Phylloscopus inornatus) as a model to understand vagrancy and its potential for the evolution of new migration routes. Movement Ecology, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-022-00345-2

Lees, A. C., Gilroy, J. (2021). Bird migration: When vagrants become pioneers. People and Current Biology, 31:24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.058

Liedvogel, M., Åkesson, S., & Bensch, S. (2011). The genetics of migration on the move. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 26:11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2011.07.009

Image credit

Top right: A Siberian Chiffchaff that has just been captured near Montpellier, France, where a few dozen individuals winter every year for the past few years. Monitoring of this population has revealed a significant proportion of adult birds (~30%) and several inter-annual returns. Most of these birds have been genotyped to ensure that they are indeed tristis © Paul Dufour.