LINKED PAPER Non-native parrot species expand the trait space of avian communities by filling empty niches in urban areas. Marcolin, F., Alba, R., Mammola, S., Assandri, G., Ilahiane, L., Rubolini, D., Reino, L. & Chamberlain, D.(2026) IBIS.VIEW

In a residential street in Florence, a Hooded Crow (Corvus cornix) clings to the trunk of a plane tree. It repeatedly tries to reach inside a nest cavity where a female Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) has just disappeared (Figure 1). The crow is not competing for the nesting site — Hooded Crows do not nest in cavities — but is likely responding to a behavioural cue, attempting to prey on eggs it assumes are already inside. In this case, its assumption was wrong: the parakeet had not yet laid. The brief encounter, however, is emblematic of the kinds of novel interactions that increasingly occur in urban environments.

Figure 1. A Hooded Crow (Corvus cornix) attacking a female Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) while the male is trying to protect her (city of Florence, Italy) © Riccardo Alba.

Figure 1. A Hooded Crow (Corvus cornix) attacking a female Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) while the male is trying to protect her (city of Florence, Italy) © Riccardo Alba.

Cities bring together species with very different evolutionary histories, ecological strategies and behavioural traits. Some of these species are native, while others have been introduced by humans and have established self-sustaining populations (Russell & Blackburn, 2017). Understanding how such non-native species fit into urban communities is a challenge in ecology, and leads us to a key question: how do they manage to persist in the first place?

Our recent study addressed this question by focusing on two non-native parrots that are common in many European cities, the Ring-necked Parakeet and the Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) (Figure 2). Rather than assessing their impacts, we examined the mechanisms that allow these species to establish within urban bird communities, asking whether they do so by sharing similar ecological characteristics with native species, or by occupying parts of the ecological niche space that are otherwise “empty” in cities.

Figure 2. A Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) in the city of Rome © Riccardo Alba.

Figure 2. A Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) in the city of Rome © Riccardo Alba.

Urban environments are ideal systems in which to explore this question. Human activities profoundly modify habitats, alter resource availability and reshape species interactions. As a result, urban bird communities are often simplified, dominated by a limited set of adaptable species. This simplification can reduce competition for some resources, but it may also leave parts of the ecological niche space underused, creating opportunities for species with different ecological strategies (Sol et al., 2012).

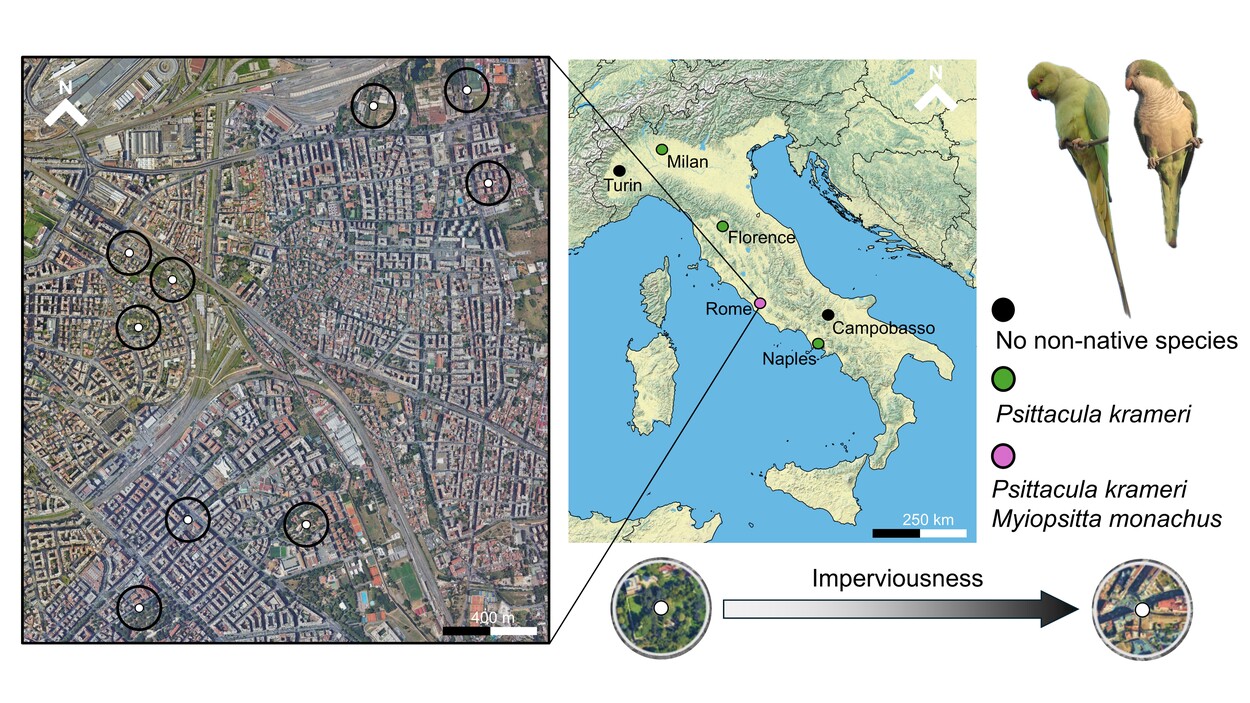

To investigate this idea, we surveyed terrestrial bird communities along an urbanisation gradient in six Italian cities: Turin, Milan, Florence, Rome, Naples and Campobasso. We conducted standardised point counts during both the breeding season and winter, recording species composition and abundance at 220 locations spanning urban green spaces, transitional areas and more densely built environments (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Location of the six cities surveyed along the Italian peninsula (right) represented by different colours depending on the presence (green and purple dot) or absence (black dot) of non-native parakeet species. An example of the study design (left) point counts (white dots) and the 100-m buffer (dark circle) across different urbanization levels (imperviousness) is shown for the city of Rome. Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameria) and Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) © Paolo Vacilotto. Satellite imagery © Google Maps (2025).

Figure 3. Location of the six cities surveyed along the Italian peninsula (right) represented by different colours depending on the presence (green and purple dot) or absence (black dot) of non-native parakeet species. An example of the study design (left) point counts (white dots) and the 100-m buffer (dark circle) across different urbanization levels (imperviousness) is shown for the city of Rome. Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameria) and Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) © Paolo Vacilotto. Satellite imagery © Google Maps (2025).

We adopted a functional approach, reconstructing the ecological niche space of each bird community. Instead of focusing on species identity alone, this approach considers the characteristics that determine how species interact with their environment, such as diet, foraging behaviour, habitat use and life-history strategies. By mapping communities into a multidimensional ecological niche space, we were able to test whether the presence of non-native parrots was associated with differences in the spread and composition of ecological strategies within urban bird communities.

In cities where parrots are established — Milan, Florence, Rome and Naples — communities tended to occupy a broader ecological niche space when parrots were present. In practical terms, parrots appeared to exploit ecological roles that were weakly represented or absent among native urban birds, rather than strongly overlapping with them.

This pattern emerged in both the breeding season and winter, but it was particularly evident during winter, when resources are more limited and community composition changes due to seasonal movements (Alba et al., 2025). In contrast, bird communities in cities without established parrots — such as Turin and Campobasso —showed a narrower range of ecological strategies, especially outside the breeding season.

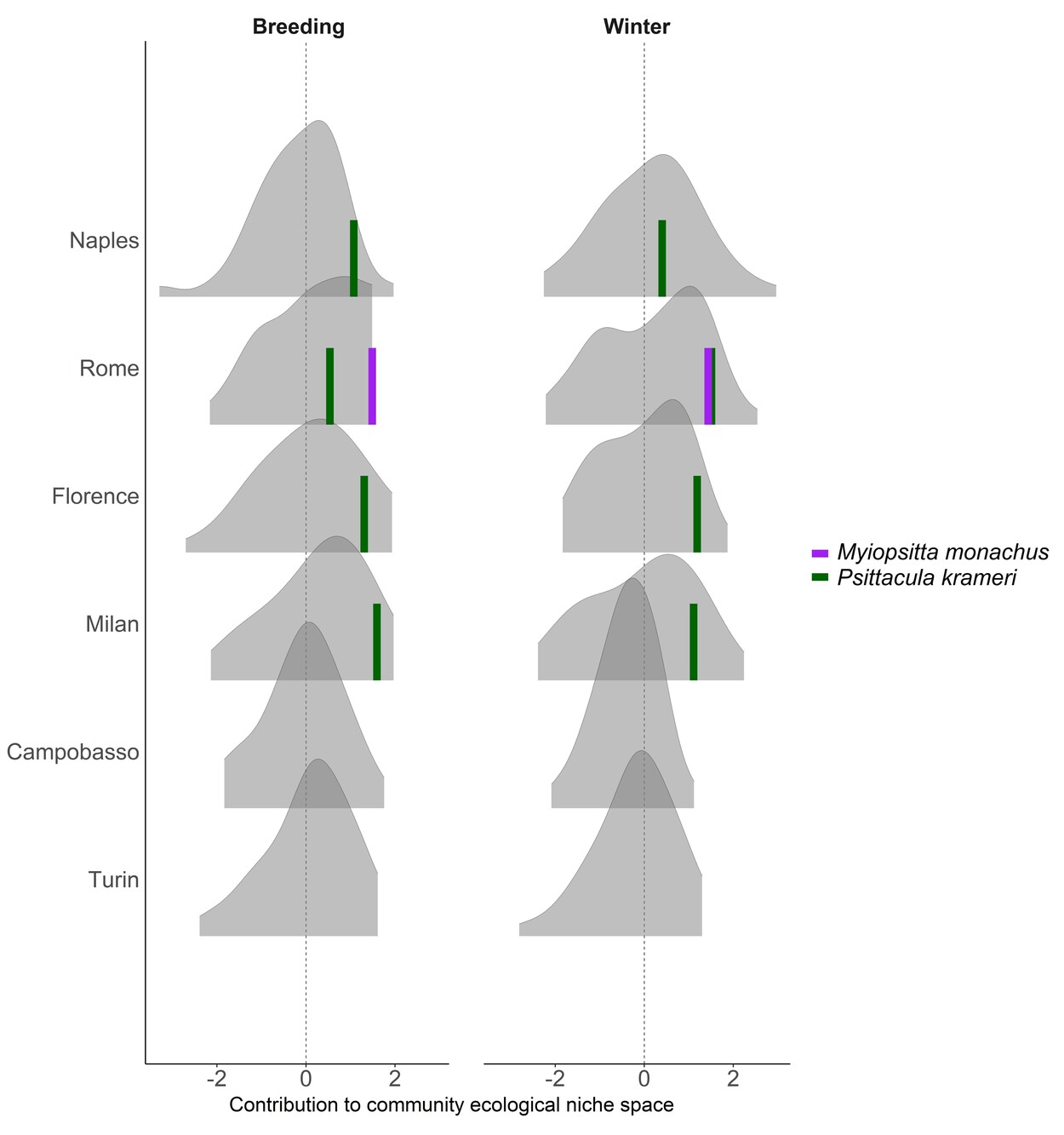

To better understand the role of parrots themselves, we also examined how much each species contributed to the overall ecological niche space of the community (Figure 4). Both parrot species consistently occupied the outer edges of the ecological niche space, indicating that they contributed disproportionately to its expansion. Importantly, when parrots were removed from invaded communities and only native species were considered, the structure of the ecological niche space of these communities remained largely unchanged. This suggests that parrots are not reshuffling or replacing the ecological roles of native species but are instead adding new ways of using urban resources to communities that were already functionally simplified by urbanisation (Marcolin et al. 2024).

Figure 4. Position of non-native parrots within the ecological niche space of urban bird communities across six Italian cities and seasons. Grey shapes show the distribution of ecological strategies of all bird species recorded within each city and season. Coloured vertical lines indicate the position of the two non-native parakeets: Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri, green) and Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus, purple). In cities where parrots are established, both species consistently occur towards the edges of the community ecological niche space, indicating the use of ecological strategies that are uncommon among native urban birds.

Figure 4. Position of non-native parrots within the ecological niche space of urban bird communities across six Italian cities and seasons. Grey shapes show the distribution of ecological strategies of all bird species recorded within each city and season. Coloured vertical lines indicate the position of the two non-native parakeets: Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri, green) and Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus, purple). In cities where parrots are established, both species consistently occur towards the edges of the community ecological niche space, indicating the use of ecological strategies that are uncommon among native urban birds.

These findings should not be interpreted as evidence that non-native parrots have no ecological impacts. Interactions such as attempted predation, competition for resources and aggressive encounters do occur, and impacts have been documented (Hernández-Brito et al. 2018).

From this perspective, cities may act as centres of establishment for non-native species (Cardador et al. 2022). Altered habitats, reduced biotic resistance and underused ecological niche space can increase the probability that introduced species persist locally, potentially facilitating their spread into other environments. Understanding these mechanisms is a crucial step towards informed management, allowing discussions about impacts and interventions to be grounded in ecological processes rather than assumptions.

The interaction between a Hooded Crow and a Ring-necked Parakeet in Florence is therefore a reminder that urban ecosystems are dynamic systems where novel interactions emerge. By studying how species assemble and persist in cities, we can better understand not only biological invasions, but also the broader ways in which biodiversity responds to rapid environmental change.

References

Alba, R., Marcolin, F., Assandri, G., Ilahiane, L., Cochis, F., Brambilla, M., … & Chamberlain, D. 2025. Different traits shape winners and losers in urban bird assemblages across seasons. Sci. Rep. 15:16181.VIEW

Cardador, L., Tella, J.L., Louvrier, J., Anadón, J.D., Abellán, P. & Carrete, M. 2022. Climate matching and anthropogenic factors contribute to the colonization and extinction of local populations during avian invasions. Divers. Distrib. 28:1908–1921.VIEW

Hernández-Brito, D., Carrete, M., Ibáñez, C., Juste, J. & Tella, J.L. 2018. Nest-site competition and killing by invasive parakeets cause the decline of a threatened bat population. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5:172477.VIEW

Marcolin, F., Segurado, P., Chamberlain, D., & Reino, L. 2024. Testing the links between bird diversity, alien species and disturbance within a human‐modified landscape. Ecography. e06886.VIEW

Russell, J.C. & Blackburn, T.M. 2017. The rise of invasive species denialism. Trends Ecol. Evol. 32:3-6.VIEW

Sol, D., Bartomeus, I. & Griffin, A.S. 2012. The paradox of invasion in birds: competitive superiority or ecological opportunism? Oecologia 169:553–564.VIEW

Image credit

Top right and featured image: Monk Parakeet © Riccardo Alba