LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Variety in responses of wintering oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus to near-collapse of their prey in the Exe Estuary, UK. Morten, J. M., Burrell, R. A., Frayling, T. D., Hoodless, A. N., Thurston, W., & Hawkes, L. A. 2022 Ecology and Evolution. doi: 10.1002/ece3.9526 VIEW

The Exe Estuary, Devon, UK is an internationally important estuary that is well protected with Ramsar, Special Protection Area (SPA) and Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) designations. During the winter months, there are thousands of visiting birds across the mixture of mud, sandbanks and pasture habitats, including approximately 1,500 Eurasian Oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus; hereafter oystercatchers). The majority of this migratory population arrive to overwinter by September and leave in February to breed elsewhere in north western Europe. In the summer months around 200 non-breeding juveniles (less than 1 year old) and sub-adults (between 1 and 3 years old) stay behind. Oystercatcher populations are declining across their range, but the overwintering Exe population has declined more rapidly over the last couple of decades than at other UK sites (Frost et al. 2021).

Figure 1 Exe Estuary Eurasian Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus) ringing scheme .

A new ringing scheme was started in February 2018 (Figure 1) and over the next several years ringers, volunteers, wardens, and scientists collaborated to capture over 300 oystercatchers in the Exe Estuary, more than 20% of this population. The overarching aim of this long-term study was to unravel the causes of the population decline, which is a complex question, and likely due to many factors. In this part of the project, we addressed the foraging behaviours of the oystercatchers. Over the last few decades their once preferred food of mussels have all but disappeared from the Exe Estuary. Here we asked where and what are they feeding on, and are they having to travel outside of the protected area to find food?

Over a four-year period, 24 oystercatchers were tracked using GPS devices to understand the areas that they used in the estuary and beyond, as well as how consistent they were in feeding areas each year. Field observations during the winter months complemented the location data and helped us to understand what oystercatchers were eating and how efficiently they could find and eat bivalves and worms. Prey were sampled in the estuary and neighbouring fields to build a picture of the present-day prey landscape in the Exe Estuary (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Data collection during this project in the Exe Estuary: field observations of foraging behaviour occurred throughout the winter (left top and bottom), tracking data were remotely transmitted to a base station (top right), and prey distribution and abundance were sampled in the estuary and neighbouring fields (bottom right).

Generally, the tracked oystercatchers remained within the Exe Estuary throughout the winter, with over 90% of recorded locations in the SPA boundary. There was high fidelity to feeding areas within the estuary, with no changes in where individual oystercatchers visited during early (Oct – Dec) and late (Jan – Mar) winter. Ten of the twelve oystercatchers with tracking data for multiple years also visited the same areas each year.

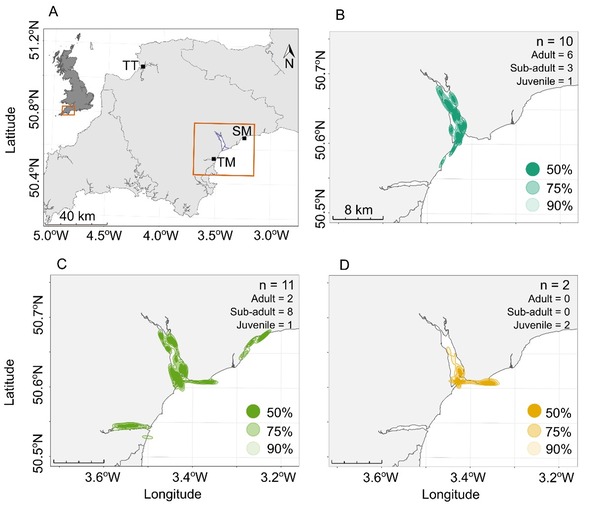

Figure 3 Home ranges of 24 oystercatchers tracked in the Exe estuary (A) over three winter periods: (B) 2018/19, (C) 2019/20 and (D) 2020/21. Eurasian Oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus) fed in areas outside of the Exe estuary, including Teignmouth (TM) and Sidmouth (SM).

Oystercatchers are faithful to their overwintering and breeding sites, with little flexibility in moving elsewhere. However, following food declines in an estuary in Wales, some oystercatchers also moved elsewhere to forage (Bowgen et al. 2022). In the Exe Estuary population, sub-adults and juvenile were more likely to visit areas outside the protected area, either visiting the neighbouring Teign estuary, or near-by beaches (Figure 3). They were also more likely to feed in the north of the estuary, which had poorer oystercatcher feeding conditions than the south. In the north, prey were more likely to be estuarine worms and did not contain as many calories as in the more dominant cockles in the south of the estuary.

This work highlights the benefits of using biologging technology in combination with field behavioural observations. The project is ongoing, with future tracking device deployments in other estuaries to understand potential connectivity. Ring reads are essential to the future success of this work, and we are extremely grateful to everyone who can assist us in this endeavour. You can report ring reads at the Devon and Cornwall Wader Ringing Group website here.

To submit a ring read, please visit this link.

References

Bowgen, K.M., Wright, L.J., Calbrade, N.A., Coker, D., Dodd, S.G., Hainsworth, I., Howells, R.J., Hughes, D.S., Jenks, P., Murphy, P.D., Sanderson, W.G., Taylor, R.C. & Burton, N.H.K. 2022. Resilient protected area network enables species adaptation that mitigates the impact of a crash in food supply. Marine Ecology Progress Series 681: 211-225. VIEW

Frost, T.M., Calbrade, N.A., Birtles, G.A., Hall, C., Robinson, A.E., Wotton, S.R., Balmer, D.E. & Austin, G.E. 2021. Waterbirds in the UK 2019/20: the wetland bird survey. BTO/RSPB/JNCC, British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford, England.

Image credit

Top right: Haematopus ostralegus © Andreas Trepte CC BY SA 2.5 Wikimedia Commons.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.