LINKED PAPERS  Predicting anthropogenic food supplementation from individual tracking data. Oppel, S., Heiniger, N., Scherler, P., van Bergen, V.S., Guelat, J., Weibel, R., Grueblet, M.U. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13359. VIEW

Predicting anthropogenic food supplementation from individual tracking data. Oppel, S., Heiniger, N., Scherler, P., van Bergen, V.S., Guelat, J., Weibel, R., Grueblet, M.U. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13359. VIEW

Extracting reproductive parameters from GPS tracking data for a nesting raptor in Europe. Oppel, S., Beeli, U.M., Gruebler, M.U., van Bergen, V.S., Kolbe, M., Pfeiffer, T., Scherler, P. 2024. Journal of Avian Biology. DOI: 10.1111/jav.03246. VIEW

Technical progress is constantly improving the way we study wildlife. For the last 2 decades devices to track the movements of animals have become smaller and more powerful, and vastly increased our understanding when, where and how individuals move through their environment. But besides knowledge on the movements of animals, new analyses can also extract demographic information from such data that help us to understand why populations are increasing or decreasing.

Figure 1. A Red Kite equipped with a solar-powered GPS transmitter © Patrick Scherler.

Wildlife populations are generally regulated by how many individuals survive from one year to the next, and by how many offspring are produced each year. To estimate the productivity of a bird population, researchers often spend many weeks in the field, trying to find nests, and then monitoring the broods until the young birds fledge. This can be very labour-intensive and may require multiple observers in remote locations for extended periods.

Understanding how people or environmental conditions affect wildlife populations can be even more complicated. For example, to understand why productivity was unusually high or low in a particular year, many other data on potential factors that may affect productivity would need to be gathered, which can be very difficult.

However, if individuals have been equipped with a tracking device that records their locations several times a day, then the movements of the birds themselves can be used to estimate whether they breed and raise offspring, and how they may respond to environmental factors.

Two new papers by the Swiss Ornithological Institute now provide an example how researchers can assess the effects of human activities on Red Kites – a widespread raptor species endemic to Europe. Red Kites are very popular birds, and many people enjoy feeding them to view these stunning creatures from their garden (Orros and Fellowes 2015). However, so far it has been challenging to understand whether the birds benefit from being fed.

Figure 2. Red Kites are frequently fed in gardens © Emmi Birch.

We used the tracking data of hundreds of Red Kites in Switzerland to detect locations where Red Kites are likely being fed by humans. Besides telemetry data, the team observed and talked to hundreds of residents in a study area in western Switzerland, and meticulously mapped where Red Kites were provided with anthropogenic food supplements (including refuse, compost, livestock remains, etcetera) (Cereghetti et al. 2019). Red Kites frequently return to places where food is regularly provided, and those movement patterns could be diagnosed in tracking data of individuals. Those areas where multiple individuals exhibited a behaviour that was characteristic of attending a feeding site were most likely to represent locations where people provided food for Red Kites (Welti et al. 2019). The models were successful, and correctly detected 85% of known feeding sites.

Figure 3. Map of correctly predicted (green) and missed (red) food supplementation sites based on Red Kite tracking data – open the interactive map here.

Using all the Red Kite tracking data from Switzerland over the past 9 years, the team was then able to create a map where anthropogenic food provisioning is likely. This map layer can be used to quantify how much time individual Red Kites spent in the vicinity of feeding sites – and relate their individual fitness to their relative use of anthropogenic feeding sites.

In another paper published this month in the Journal of Avian Biology we provided a tool to estimate whether Red Kites bred and raised offspring – again solely based on the information contained in the tracking data. Using a similar concept as for the detection of feeding sites, birds that have a nest frequently return to the same location and spend a lot of time in the vicinity of their nest.

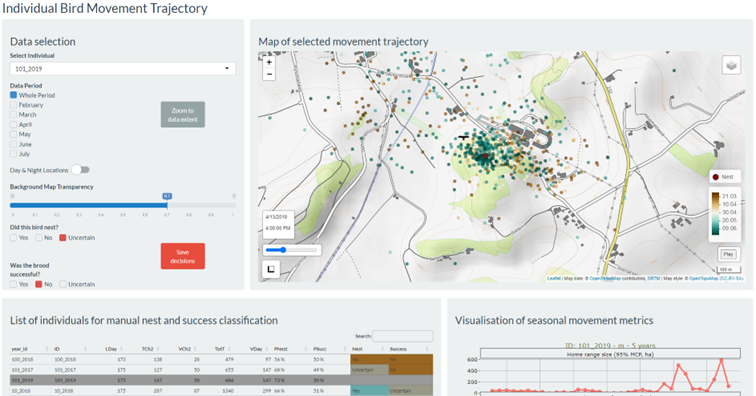

The new ‘NestTool’ allows researchers to estimate whether individuals settled in a home range, started breeding, and raised offspring based on their tracking data. The tool also provides a graphical interface to inspect cases that cannot be reliably classified, so that users can manually annotate uncertain cases. A field app even allows researchers to find nests during the breeding season based on the most recent tracking data.

Figure 4. Graphical user interface of the NestTool to assist researchers in deciding whether a tracked individual initiated a nesting attempt and raised offspring.

These two new tools together now facilitate investigations whether the frequent use of anthropogenic food subsidies increases the productivity of Red Kites or not. Future investigations will combine these approaches with the flexible migration strategy of Red Kites in Switzerland (Witczak et al. 2024), to examine whether the recent increase of the Swiss Red Kite population may have been caused by people feeding kites, by climatic changes, or a combination of several factors.

You can find more information on the project at the Swiss Ornithological Institute.

References

Orros, M.E., Fellowes, M.D.E. (2015). Widespread supplementary feeding in domestic gardens explains the return of reintroduced Red Kites Milvus milvus to an urban area. IBIS 157(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12237

Cereghetti, E., Scherler, P., Fattebert, J., Gruebler, M.U. (2019). Quantification of anthropogenic food subsidies to an avian facultative scavenger in urban and rural habitats. Landscape and Urban Planning 190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103606

Welti, N., Scherler, P., Gruebler, M.U. (2019). Carcass predictability but not domestic pet introduction affects functional response of scavenger assemblage in urbanized habitats. Functional Ecology 34(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13469

Witczak, S., Kormann, U., Schaub, M., Oppel, S., Gruebler, M.U. (2024). Sex and size shape the ontogeny of partial migration. Journal of Animal Ecology 93(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14051

Image credit

Top right: Red Kites are frequently being fed in gardens © Stuart Gay.