LINKED PAPER

Estimating the mass of the Great Auk and its egg. Montgomerie, R.D., Birkhead, T.R. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13350 VIEW

Imagine you are a contestant on the TV quiz show ‘Only Connect’. You are presented with four bird names and asked what they have in common:

- Rodrigues Solitaire Pezophaps solitaria

- Dodo Raphus cucullatus

- Nechisar Nightjar Caprimulgus solala

- Great auk Penguinus impennis

You might first assume that they are all extinct, but the Nechisar nightjar might not be (as far as we know).

The correct answer is that for none of these four species is their body mass known. It’s easy to understand why no body mass information exists for the solitaire, Dodo or Great Auk: no-one bothered to weigh them before they became extinct. In the nightjar’s case, no-one has ever seen or handled an entire bird: only a single wing, has been recovered from a decomposing specimen found in 1990 in Nechisar National Park in Ethiopia.

Figure 1. Nechisar Nightjar wing from Natural History Museum © R J. Safford CC-BY 4.0 Wikimedia Commons.

Why would you want to know the body mass of these, or any other, bird species? That we do is exemplified by the fact that most handbooks (e.g. Birds of the Western Palearctic) include information on body mass for each species, and there is even a handbook that lists the body mass of around 8000 species (Dunning 2007). Why? Perhaps the main reason we are interested in avian body mass is to be able conduct comparative studies in which traits such as brain size, testes size, or egg size can be scaled relative to body size, since it has long been known that relative organ size provides an important index of functionality. Body size is also an excellent predictor of many ecological and life history traits (Peters 1983).

Estimating the body mass of species that no longer exist, or, like the Nechisar Nightjar, where an intact specimen has never been seen, would seem to pose a challenge. However, we have a wing of this nightjar, and it is known that wing length is a reasonable, predictor of body mass, a least among closely related species. Nightjars are also fairly uniform in their conformation (excluding elaborate plumes in some species), varying mainly in size and plumage patterns. It is straightforward then to plot the relationship between wing length and body mass for all known nightjar species to obtain an estimate of the Nechisar nightjar’s likely body mass (76g). Although that nightjar’s wing is long relative to other Ethiopian night jar species, it falls well within the range of known nightjar wing lengths. And since the species is probably not extinct, someone may catch one and weigh it, so this estimate can be verified or corrected.

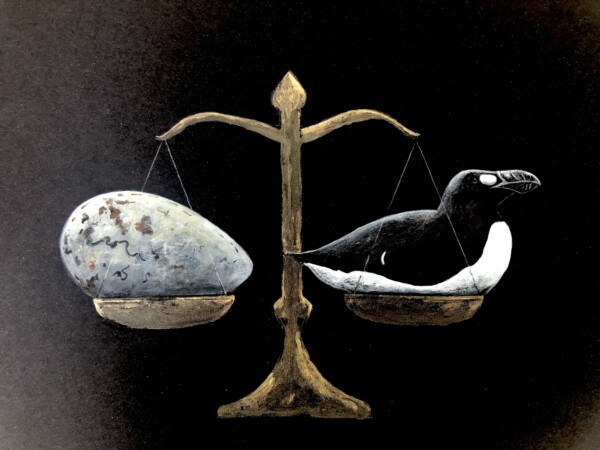

Estimating the body mass of the Dodo, solitaire or Great Auk is more difficult. Our paper focuses on the Great Auk, extinct since 1844. Even though tens of thousands were slaughtered for their meat or feathers, and over 100 specimens were collected for museums (of which 70-80 skins still exist), no one ever weighed an intact bird or an egg. A single anecdotal account from 1808, together with some later estimates, suggested that the great auk weighed between 4,500 and 5000g. The mass of its (fresh) egg has been estimated at 327 or 372g using comparative methods.

Figure 2. Scale with auk and egg © Tim Birkhead.

One cannot obtain an estimate of the Great Auk’s body mass by following the procedure above that we used to estimate the nightjar’s body mass, for two main reasons. First, the Great Auk was larger than any extant member of the twenty-two-strong auk family (Alcidae), making extrapolation risky and predicted values subject to wide confidence limits. Second, because the great auk was flightless, the relative size of its wings and pectoral girdle are very different from those of the extant auks. A more careful and critical approach was therefore needed. Using tibiotarsus and femur length in one analysis and egg volume in another, while controlling for phylogeny, we obtained a mean body mass estimate of 3560 g, which is around 25% less than previously thought. We also estimated the fresh mass of the Great Auk’s egg to be 360 g using accurate measures of egg volume from 51 intact eggshells and similar comparative procedures using data from the extant alcid species.

Together, these two new measures better inform our speculation about several aspects of the great auk’s lifestyle, including its developmental mode. A previous study (Houston et al. 2010), for example, used a model of time and energy budgets to suggest that the mode of development of the Great Auk’s chick was probably a type of semi-precocial development called ‘intermediate’ just as in its closest relatives: the Razorbill Alca torda, Common Guillemot Uria aalge and Brünnich’s Guillemot (see also Birkhead 2021). Our new estimates of the Great Auk’s egg and body mass confirms this mode of chick development as the Great Auk’s egg weighed about 10% of adult body mass, close to the values for the other species with this developmental mode. Other studies have used the presumed mass of the Great Auk (4500-5000 g) to estimate the body mass of other extinct alcids (Smith 2016) and to estimate the year-round energy expenditure of the Great Auk (Dunn et al. 2023). Our new estimate should help to inform that research.

References

Birkhead, T.R. 2021. The chick-rearing period of the Great Auk: a mystery solved. British Birds 114: 27-37.

Dunn, R.E., Duckworth, J. & Green, J.A. 2023. A framework to unlock marine bird energetics. Journal of Experimental Biology 226: jeb246754.

Houston, A.I., Wood, J. & Wilkinson, M. 2010. How did the Great Auk raise its young? Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23: 1899–1906.

Peters, R.H. 1983. The Ecological implications of body size. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Smith, A. 2016. Evolution of body mass in the Pan-Alcidae (Aves, Charadriiformes): the effects of combining neontological and paleontological data. Paleobiology 42: 8-26.

Image credits

Top right: Great Auk and chick © David Quinn from Birkhead (2021).

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here