LINKED PAPER

Pronounced long-term trends in year-round diet composition of the European shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis. Howells, R.J., Burthe, S.J., Green, J.A., Harris, M.P., Newell, M.A., Butler, A., Wanless, S., & Daunt, F. 2018. Marine Biology. DOI: 10.1007/s00227-018-3433-9. VIEW

Many seabird populations are declining globally (Paleczny et al., 2015). Diet composition is a key determinant of seabird demography, affecting the number of chicks they raise, their body condition and survival. As such, seabird diet has been well studied, utilising a wide range of methods including regurgitated food, stable isotopes, fatty acid analysis, dissections of shot or dead birds, photographs and visual observations (reviewed in Barrett et al. 2007).

The majority of seabird diet studies investigate chick diet during breeding, when samples are relatively easy to collect or observe from birds at their colonies (Figure 1). Due to the difficulties of obtaining diet samples away from the breeding colony, much less is known regarding the diet of seabirds at other times of year, particularly during winter, when the mortality of seabird mortality occurs. A number of studies have identified substantial changes in seabird diet during breeding over the past 30 or so years (Gaston and Elliott, 2014; Green et al., 2015; Church et al., 2018). However, whether non-breeding diet has matched these trends remains unknown and is a key knowledge gap in our understanding of the factors driving seabird population declines.

Figure 1 An Atlantic Puffin Fratercula arctica with a beak full of sandeels © Centre for Ecology Hydrology

Several North Sea seabird populations are declining rapidly (JNCC, 2016). These declines have predominantly been observed in species that are highly dependent on lesser sandeel Ammodytes marinus, with climate-mediated changes in the availability and quality of this key prey believed to be an important driver (Wanless et al., 2005, 2007). The European shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis is one such species, which has displayed substantial declines of ~50% in the UK since the 1980s and has recently had its conservation status updated to Red (Eaton et al., 2015).

The shag population resident on the Isle of May National Nature Reserve, Scotland has been studied extensively over the past three decades as part of the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology’s Isle of May Long Term Study. Birds in this population were traditionally considered sandeel specialists, but recent research shows that the diet of chicks in this population has diversified over the past three decades (Howells et al., 2017). However, how the diet of shags throughout the annual cycle has changed over this period remains unknown.

Like owls, shags regularly regurgitate indigestible prey remains in the form of pellets. These can be collected at accessible roosts, providing a rare opportunity to quantify diet composition throughout the year. Once collected each pellet is taken back to the lab and placed in biological washing powder. This dissolves away the mucus and any soft tissue, leaving only hard structures, such as bones. These are then sifted through to find otoliths (ear bones), which are species specific and allow the number and diversity of different prey types in each pellet to be identified.

Figure 2 A fresh shag pellet © Centre for Ecology Hydrology

By inspecting roost sites during routine visits to the Isle of May conducted throughout the year 5,888 pellets containing a whopping 495,239 fish otoliths were collected over three decades (1985–2014). This allowed us to address the following questions:

- What was the year round diet composition of shags at this colony over three decades?

- Have any dietary trends differed between the breeding and non-breeding periods?

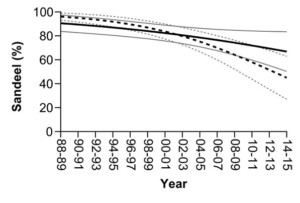

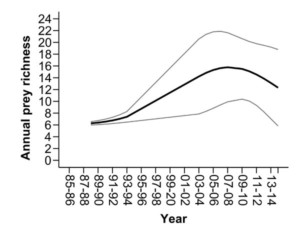

We identified dramatic changes in the diet of full-grown shags on the Isle of May over the past three decades. This population were predominantly sandeel specialists in the 1980s-90s, but the occurrence in the diet reduced dramatically over the study (Figure 3). Over the same period, the number of prey types consumed per year doubled from an average of six to 12, including an increasing frequency of Cod Fishes, Cottids and Right-eye Flounders (Figure 4). Crucially, the diet changes were apparent throughout the annual cycle, in both the breeding and non-breeding periods. Furthermore, the decline in sandeel frequency within pellets was more marked during the non-breeding period (96% in 1988 to 45% in 2014), than the breeding period (91–67%; Figure 3).

Figure 3 Temporal trends in the frequency of sandeel occurrence within pellets between 1985 and 2014. Solid line indicates breeding period and dashed line indicates the non-breeding period. Black and grey lines indicate trends and dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals, respectively

Figure 4 Temporal trends the number of prey types consumed each year (annual prey richness) between 1985 and 2014. Black and grey lines indicate trends and dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals, respectively

We provide the first evidence for long-term trends in the diet composition of a marine top predator during both the breeding and non-breeding periods, suggesting that prey availability has changed throughout the annual cycle. This is important as the non-breeding period is of critical importance to shag demography, since this is the period in which the majority of mortality occurs (Figure 5). As shags appear to exist through the dark and inclement winter months on an energetic knife-edge, changes in winter diet composition may have impacts on individual condition and overwinter survival. Finally, shags are considered to be one the North Sea seabirds least vulnerable to changes in sandeel abundance (Furness and Tasker, 2000). Therefore, if the dietary trends reflect the changing availability of sandeels and other prey types, this may have important implications for other seabird species that, unlike shags, have a limited capacity to switch prey.

Figure 5 A dead shag found during a mass mortality (“wreck”) event © Centre for Ecology & Hydrology

References

Barrett, R. T., Camphuysen, K., Anker-Nilssen, T., Chardine, J. W., Furness, R. W., Garthe, S., Hüppop, O., Leopold, M. F., Montevecchi, W. A. and Veit, R. R. 2007. Diet studies of seabirds: A review and recommendations. ICES Journal of Marine Science 64: 1675–1691. VIEW

Church, G. E., Furness, R. W., Tyler, G., Gilbert, L. and Votier, S. C. 2018. Change in the North Sea ecosystem from the 1970s to the 2010s: great skua diets reflect changing forage fish, seabirds, and fisheries. ICES Journal of Marine Science. VIEW

Eaton, M. A., Brown, A. F., Hearn, R., Noble, D. G., Musgrove, A. J., Lock, L., Stroud, D. and Gregory, R. D. 2015. Birds of conservation concern 4: the population status of birds in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man. British Birds 108: 708–746. VIEW

Furness, R. W. and Tasker, M. L. 2000. Seabird-fishery interactions: Quantifying the sensitivity of seabirds to reductions in sandeel abundance, and identification of key areas for sensitive seabirds in the North Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 202: 253–264. VIEW

Gaston, A. J. and Elliott, K. H. 2014. Seabird diet changes in northern Hudson Bay, 1981-2013, reflect the availability of schooling prey. Marine Ecology Progress Series 513: 211–223. VIEW

Green, D. B., Klages, N. T. W., Crawford, R. J. M., Coetzee, J. C., Dyer, B. M., Rishworth, G. M. and Pistorius, P. A. 2015. Dietary change in Cape gannets reflects distributional and demographic shifts in two South African commercial fish stocks. ICES Journal of Marine Science 72: 771−781. VIEW

Howells, R. J., Burthe, S. J., Green, J. A., Harris, M. P., Newell, M. A., Butler, A., Johns, D. G., Carnell, E. J., Wanless, S. and Daunt, F. 2017. From days to decades: short- and long-term variation in environmental conditions affect offspring diet composition of a marine top predator. Marine Ecology Progress Series 583: 227–242. VIEW

JNCC 2016. Seabird population trends and causes of change: 1986-2015 report. Available at: https://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-3201. VIEW

Paleczny, M., Hammill, E., Karpouzi, V. and Pauly, D. 2015. Population Trend of the World’s Monitored Seabirds, 1950-2010. Plos One 10(6): e0129342. VIEW

Wanless, S., Frederiksen, M., Daunt, F., Scott, B. E. and Harris, M. P. 2007. Black-legged kittiwakes as indicators of environmental change in the North Sea: Evidence from long-term studies. Progress in Oceanography 72(1): 30–38. VIEW

Wanless, S., Harris, M. P., Redman, P. and Speakman, J. R. 2005. Low energy values of fish as a probable cause of a major seabird breeding failure in the North Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 294: 1–8. VIEW

Image credits

Featured image: An adult and juvenile European shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis © Gary Howells