Report from a BOU-funded project

What is honey-hunting? What is human-honeyguide mutualism? These are interesting questions you may find yourself asking. Wild honey gathering or honey-hunting is an ancient cultural tradition that is widespread across Africa. A motivated local ‘honey-hunter’ leaves their house and walks to the wild to obtain honey from wild bees’ nests (mostly nests of Apis mellifera). The honey obtained from the bees’ nests is used for food, medicine to cure and/or treat ailments, and/or to sell for money for personal or family needs.

In Africa, many local customs and traditions are associated with honey-hunting. For instance, in parts of Africa, honey hunters co-operate with the incredible Greater Honeyguide (Indicator indicator) to access the content of bee nests. The Greater Honeyguide approaches a honey-hunter, sounds a loud distinct chattering call to seek the attention of the honey-hunter. From there they fly from tree to tree in the direction of the bee nest until the honey-hunter finds the nest. This happens because the Greater Honeyguide cannot access the bees’ nest on it own without the help or assistance of a human.

Figure 1 Anap interviewing a man from the Afizere cultural group © Gabriel Atsen.

The skilled honey-hunter opens the bee nest and harvests fresh honey while the honeyguides access the wax combs. It is a win-win for both parties involved! However, this remarkable mutualism is declining across Africa, and we do not know the full extent of where this mutualism occurs. Does this mutualistic relationship even exist in Western Africa? If so, is it known to the scientific community? How about Nigeria, does honey-hunting exist, and do honey-hunters use the Greater Honeyguide to find bee nests? These were questions we sought to find the answers to.

To answer these questions, we interviewed 58 people across eight villages (at least 10 km apart) occupied by people of mixed cultural backgrounds. We set 108 questions and asked participants a set of questions about their honey-hunting culture and activities, the use of honey, honey-hunting timing and experience, rewards provided to Greater Honeyguides, honey-hunting signals, and other honeyguide behaviours, honey hunting sustainability and whether there has been any change in these over time.

What did we find?

We found that honey-hunting with honeyguides occurs in Nigeria, and this is the first of its kind in West Africa. Among the 58 interviewees, we found that honey is important across all cultures, and is used for food, medicine and sold for money. We found that the Fulani and Mambila cultural groups are most knowledgeable about the Greater Honeyguide.

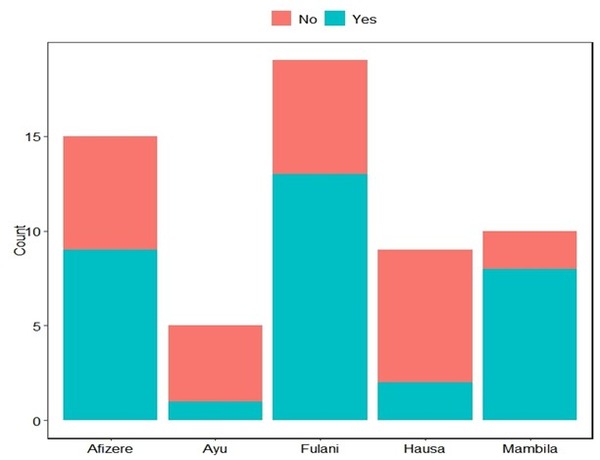

Figure 2 Stacked bar plot showing participants’ responses about their knowledge of the Greater Honeyguide.

The interviewed participants said that the Greater Honeyguide has a positive cultural significance as it is seen as a good luck charm. Some other respondents reported that they use the bird to find bees nests on honey-hunting trips and also actively reward the honeyguide with brood and/or wax after being guided.

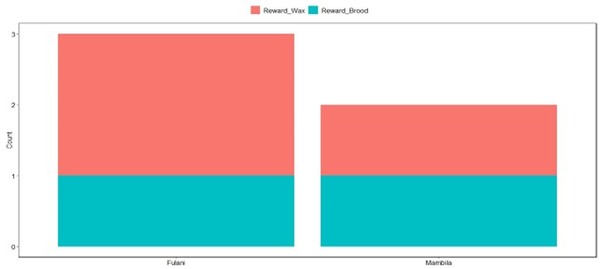

Figure 3 Stacked bar plots showing participants’ responses about rewarding the Greater Honeyguide after being guided.

Unlike in other honey-hunting cultures elsewhere in Africa, however, Nigerian honey-hunters said that they do not use sounds to communicate with the greater honeyguide. Some interviewees reported that the Greater Honeyguide leads people to dangerous animals and places. Approximately 64% of the participants reported that they get their honey from wild bees. All the cultural groups knew about the Greater Honeyguide and have different local names for the species; Fulanis: Gundaru, Hausa: Tsuntsun Zuma, Mambila: Nyinyip, Afizere: Akpereng. The majority of participants (76%) said that they thought the practice of honey-hunting has changed since they were young. From the people that said they thought it had changed, some mentioned that it was due to loss of interest and habitat degradation. Some 77% of people thought that in particular, the role of honeyguides in honey-hunting has changed over time, which they associated with declining honeyguide populations, environmental factors and habitat degradation.

Funding

In 2022, Afan Anap Ishaku was awarded a Career Development Bursary of £2,449 for a project titled “Honeyguides, honey-eating and the current state of human-honeyguide mutualism in Nigeria”.

References

Dunne, J. et al. 2021. Honey-collecting in prehistoric West Africa from 3500 years ago. Nature Communications 2227. VIEW

Gruber, M. 2018. Hunters and guides: multispecies encounters between humans, honeyguide birds and honeybees. African Study Monographs 39: 169-187. VIEW

Laltaika, E. A 2021. Understanding the mutualistic interaction between greater honeyguides and four co-existing human cultures in northern Tanzania, Master’s thesis, Faculty of Science.

Spottiswoode, C. N., Begg, K. S., & Begg, C. M. 2016. Reciprocal signaling in honeyguide-human mutualism. Science 353: 387-389. VIEW

van der Wal, J. E., Gedi, I. I., & Spottiswoode, C. N. 2022. Awer honey-hunting culture with greater honeyguides in coastal Kenya. Frontiers in Conservation Science 2: 727479. VIEW

Wood, B. M., Pontzer, H., Raichlen, D. A., & Marlowe, F. W. 2014. Mutualism and manipulation in Hadza–honeyguide interactions. Evolution and Human Behaviour 35: 540-546. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Greater Honeyguide, Indicator indicator, male © Frans Vandewalle CC BY NC 2.0 Flickr.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.