LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

The role of wind fetch in structuring Antarctic seabird breeding occupancy at three colonies in Iceland. Schrimpf, M. & Lynch, H. 2021. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12910. VIEW

Scientific insights often start with a simple observation. While studying Gentoo Penguins (Pygoscelis papua), Michael Schrimpf and Heather Lynch noticed that their colonies appeared to be clustered in enclosed sections of the coastline. Could it be that the penguins chose these locations to be sheltered from the damaging effects of wind and waves? A survey of the literature revealed that few studies have considered the role of wind exposure in habitat selection of seabirds (Hilde et al. 2016). So, the researchers collected data on the breeding locations of several seabird species and used coastline maps to determine the strength of the prevailing winds (Humphries et al. 2017).

Wind fetch

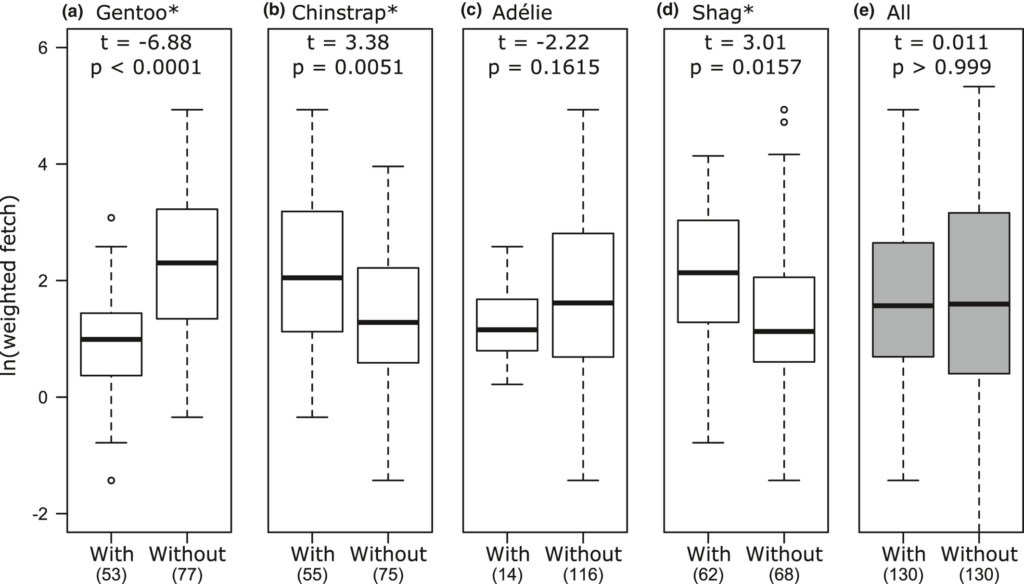

In order to quantify the effect of the wind, Schrimpf and Lynch calculated the parameter wind fetch, i.e. the distance of open water over which wind can blow uninterrupted. High fetch points to strong wind and wave action, whereas low fetch indicates calm seas with little wind. As expected, the analyses revealed a negative effect of wind fetch on the colony locations of Gentoo Penguins. Interestingly, the breeding sites of two other seabirds species – Chinstrap Penguin (Pygoscelis antarcticus) and Antarctic Shag (Leucocarbo bransfieldensis) – showed a positive relationship with wind fetch. Finally, the habitat selection of the Adélie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) seemed unaffected by the strength of winds and waves.

Figure 1. Wind fetch differences among species. The distribution of the wind-weighted fetch at breeding sites with and without each species seabird, (a) Gentoo Penguin, (b) Chinstrap Penguin, (c) Adélie Penguin and (d) Antarctic Shag, in the central-west region of the Antarctic Peninsula. Notice the signicantly lower wind fetch at breeding sites with the Gentoo Penguin, in contrast to the other species.

Explanations

What mechanism could explain these findings? The researchers offer some possible answers from the perspective of the Gentoo Penguin. First, this species is known to breed at lower elevations along the coastline, which makes them more vulnerable to the onslaught of flooding and strong winds (Volkman & Trivelpiece 1981). It would be a logical choice to build your nest in a more sheltered location. Second, Gentoo Penguins tend to make shorter foraging trips compared to the other penguin species (Kokubun et al. 2010). They are thus more affected by the physical action of the waves because they have to leave the colony more often (and Antarctic Shag can just fly over any violent waves). On a more speculative note, Gentoo Penguins might exchange visual information by leaping out of the water (an interesting hypothesis that remains to be tested, Wiemerskirch et al. 2010). This behavior will be more efficient in calmer seas. By proposing these possible explanations, this study nicely shows how a simple observation can raise many new questions.

References

Hilde, C.H., Pélabon, C., Guéry, L., Gabrielsen, G.W. & Descamps, S. (2016). Mind the wind: microclimate effects on incubation effort of an arctic seabird. Ecology and Evolution 6: 1914– 1921. VIEW

Humphries, G.R.W., Naveen, R., Schwaller, M., Che-Castaldo, C., McDowall, P., Schrimpf, M. & Lynch, H.J. (2017). Mapping Application for Penguin Populations and Projected Dynamics (MAPPPD): data and tools for dynamic management and decision support. Polar Record. 53: 160– 166. VIEW

Kokubun, N., Takahashi, A., Mori, Y., Watanabe, S. & Shin, H.C. (2010). Comparison of diving behavior and foraging habitat use between Chinstrap and Gentoo Penguins breeding in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Marine Biology 157: 811– 825. VIEW

Volkman, N.J. & Trivelpiece, W. (1981). Nest-site selection among Adélie, Chinstrap and Gentoo Penguins in mixed species rookeries. The Wilson Bulletin 93: 243– 248. VIEW

Weimerskirch, H., Bertrand, S., Silva, J., Marques, J.C. & Goya, E. (2010). Use of social information in seabirds: compass rafts indicate the heading of food patches. PLoS One 5: e9928. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Gentoo Penguins (Pygoscelis papua) | Jerzy Strzelecki | CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here