LINKED PAPER

Automated radio tracking provides evidence for social pair bonds in an obligate brood parasite. Scardamaglia, R. C., Lew, A. A., Gravano, A., Winkler, D. W., Kacelnik, A., & Reboreda, J. C. 2022. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13086. VIEW

Social monogamy, where an individual forms a social bond with one partner during the breeding season, is common among birds (Cockburn 2006). One of the primary drivers of this social mating system could be parental care. The various responsibilities associated with parenting – including nest building, incubation, and provisioning – restrict the number of partners an individual bird can effectively support (Ricklefs & Wikelski 2002). However, this reasoning does not apply to brood parasites. These species lay their eggs in the nests of other species, relieving them of the costs of parental care. Nevertheless, some brood parasites do exhibit social monogamy. In a recent study, Romina Scardamaglia and her colleagues investigated whether the Screaming Cowbird (Molothrus rufoaxillaris) is socially monogamous. And if so, why?

Social network

The Screaming Cowbird, a South-American brood parasite, specializes on the Greyish Baywing (Agelaiodes badius) as a host species (Ortega 1998). The researchers captured 28 individuals at the ‘El Destino’ reserve in Argentina and equipped them with radio transmitters. Next, they applied two methods to test for social monogamy in Screaming Cowbirds. First, they analysed the interactions between individual birds to identify potential couples. Second, they calculated the degree of overlap in home range among these individuals. These approaches revealed the presence of seven cowbird couples within the reserve.

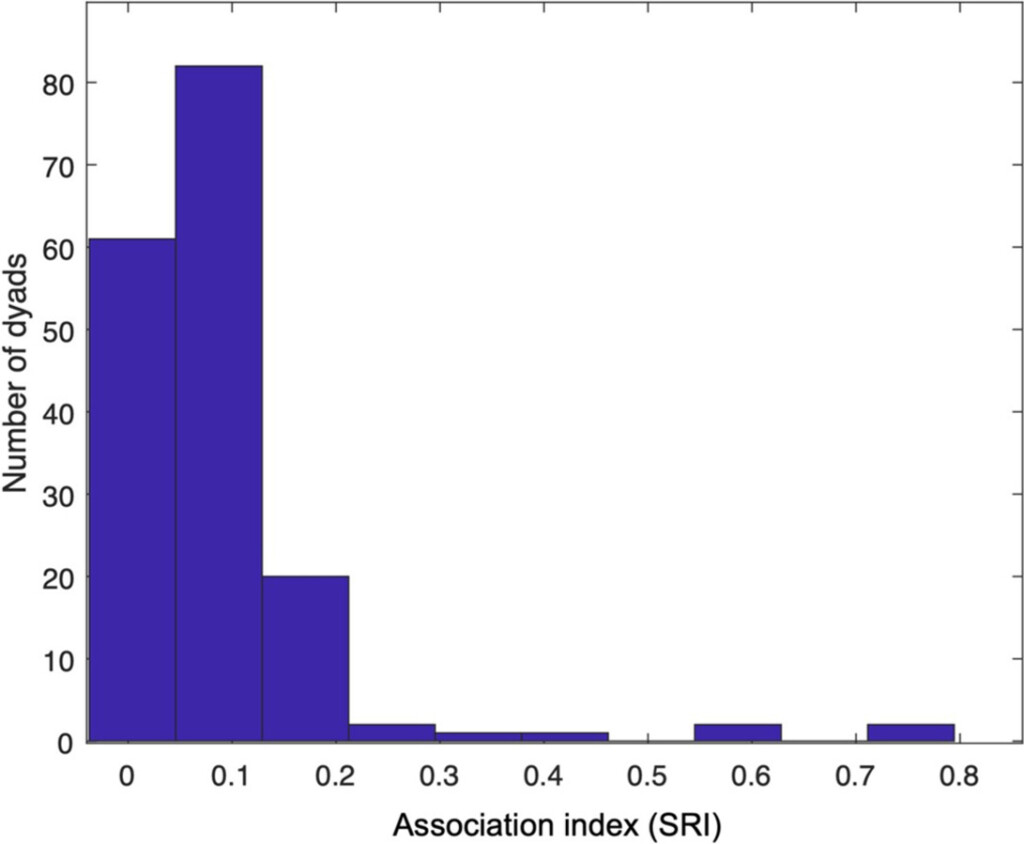

Figure 1. Association indices between all possible combinations of individuals in the reserve. A high index points to a social couple.

Mate guarding

Having established the social monogamy of Screaming Cowbirds, the researchers proposed two hypotheses to explain this behaviour: cooperative nest searching and mate guarding. The cooperative nest searching hypothesis suggests that males act as distractors, diverting attention away from females, enabling them to parasitize the nest (Hauber & Dearborn 2003). Alternatively, the male may engage in mate guarding, protecting its partner from copulation attempts by other males (Wittenberger & Tilson 1980). The mate guarding hypothesis finds support in circumstantial evidence. During capture sessions, males would perch near the trap when their partner was caught, while females did not exhibit this behaviour. However, controlled experiments are necessary to rigorously test this hypothesis and unveil further insights into the secret life of cowbirds.

References

Cockburn, A. (2006). Prevalence of different modes of parental care in birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 273: 1375– 1383. VIEW

Hauber, M.E. & Dearborn, D.C. (2003). Parentage without parental care: what to look for in genetic studies of obligate brood-parasitic mating systems. The Auk 120: 1– 13. VIEW

Ortega, C.P. (1998). Cowbirds and Other Brood Parasites. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. VIEW

Ricklefs, R.E. & Wikelski, M. (2002). The physiology/life-history nexus. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 17: 462– 468. VIEW

Wittenberger, J. & Tilson, R. (1980). The evolution of monogamy: hypotheses and evidence. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 11: 197– 232. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Screaming Cowbird (Molothrus rufoaxillaris) | Cláudio Dias Timm | CC BY-SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here