LINKED PAPER

Accuracy of nest fate classification and predator identification from evidence at nests of Least Terns and Piping Plovers. Andes, A.K., Shaffer, T.L., Sherfy, M.H., Hofer, C.M., Dovichin, D.M. & Ellis-Felege, S.N. 2019. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12629 VIEW

Understanding the population dynamics of bird species requires good estimates of several demographic factors, such as nest survival. If an ornithologist is monitoring a nest and finds it empty, she needs to deduce whether the nest failed (e.g., all chicks were taken by predators) or was successful (e.g., all chicks left the nest). Numerous methods have been developed to estimate nest survival, but there is often uncertainty about the fate of a nest when the exact series of events cannot be reconstructed (Martin & Geupel 1993, Schaffer 2004). One possibility is to deploy cameras and follow the developments at the nest continuously (Ball & Bayne 2012). However, cameras are expensive and not always feasible for small-scale monitoring projects. So, how often should you visit a nest to get a reliable estimate of nest survival?

Monitoring

Recently, a group of American researchers took advantage of a peculiar situation to address this question. Two federal agencies were monitoring nests of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) and Least Terns (Sternula antillarum) in the same area in North Dakota. One agency searched for nests twice a week with additional visits for banding adults and checking for hatched chicks. The second agency searched the area for birds and nests only once a week. The researchers monitored the nests with cameras and compared their findings with the results from both agencies. This comparison revealed that the first monitoring scheme of biweekly checks (referred to as the 3-day monitoring) was more accurate in classifying nests as failed or successful compared to monitoring once a week (referred to as the 7-day monitoring). Specifically, the 3-day monitoring strategy correctly classified 72% of the nests, while the 7-day monitoring strategy only classified 27.5% of the nests successfully.

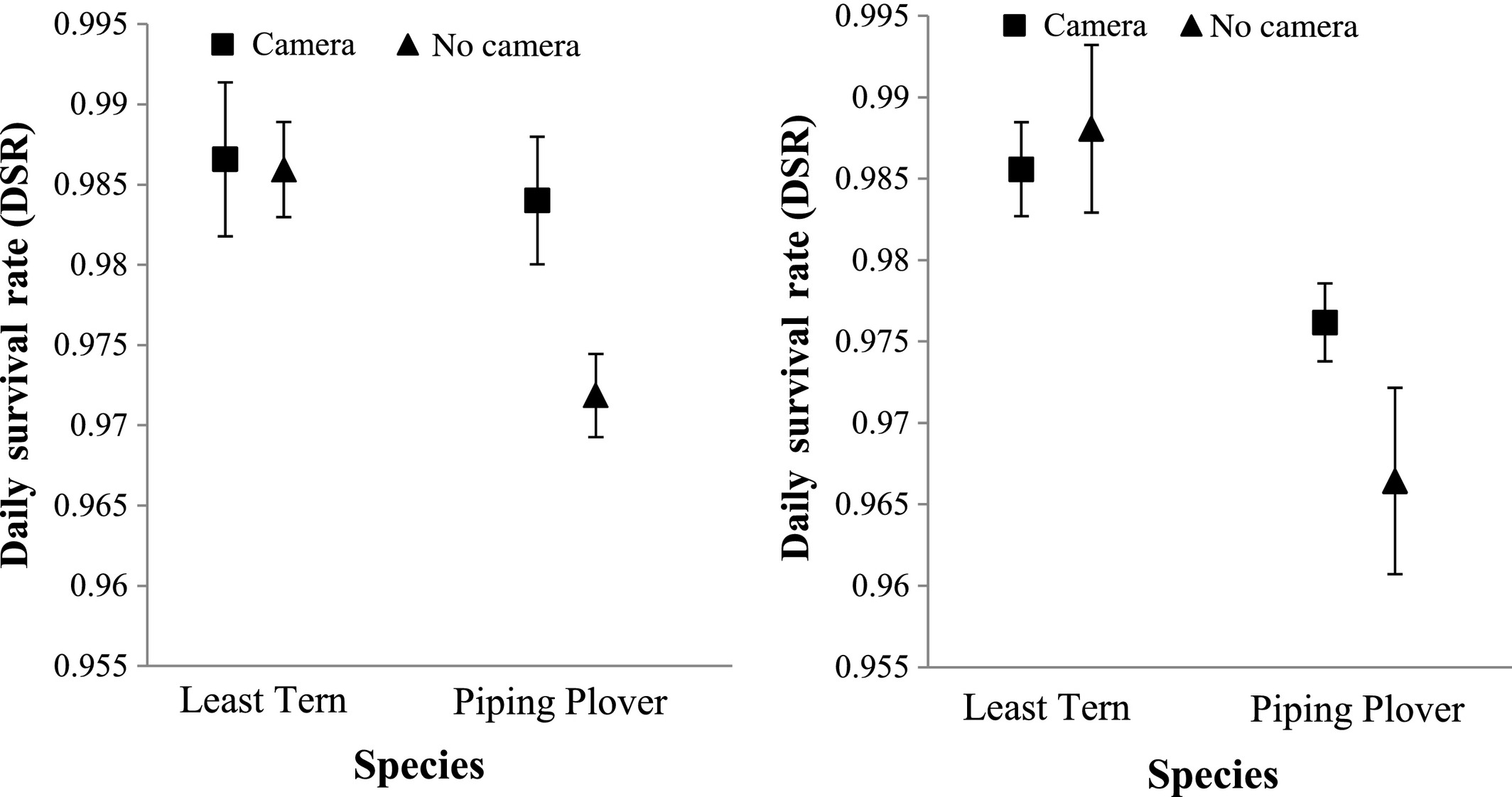

Figure 1 Daily nest survival rates of Least Tern and Piping Plover nests (part a) and sites (part b) with and without cameras on the Missouri River in North Dakota from 2013 to 2015.

Predation

Unsurprisingly, more frequent nest visits provided the best estimates of nest survival. However, if nests were predated, it was often not possible to deduce which predators ate the eggs or chicks (Larivière 1999). Here, cameras were clearly an asset. The cameras captured predation by several mammals (e.g., Red Fox Vulpes vulpes and Raccoon Procyon lotor) and birds (e.g., American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia), Bald Eagle ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus ) and Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus)). Some scientists have argued that the use of cameras can increase predation rates on nests, because predators learn to associate cameras with feeding opportunities (Pietz & Gransfors 2000). In this study, however, there were no significant differences in predation rates between nests with and without cameras. All in all, we can conclude that the use of cameras is advisable to monitor nests. If this is not financially feasible, regular nest visits are required to obtain reliable estimates of nest survival.

References

& (2012). Using video monitoring to assess the accuracy of nest fate and nest productivity estimates by field observation. Auk 129: 438– 448. VIEW

(1999). Reasons why predators cannot be inferred from nest remains. Condor 101: 718– 721. VIEW

& (1993). Nest‐monitoring plots: methods for locating nests and monitoring success. Journal of Field Ornithology 64: 507– 519. VIEW

& (2000). Identifying predators and fates of grassland passerine nests using miniature video cameras. Journal of Wildlife Management 64: 71– 87. VIEW

(2004). A unified approach to analyzing nest success. Auk 121: 526– 540. VIEW

Image credits

Featured image: Least tern Sternula antillarum | Dan Pancamo | CC BY-SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons