“You’re a woman? Because of the work you’re doing, I thought you were a man.”

This question came up before a talk I gave back in Korea, after spending four years in Mongolia working on forest and wildlife conservation. I couldn’t help but respond to the young man’s simple, eager, innocent curiosity, full of warmth and excitement. I often receive these questions because my work isn’t really seen as representative of women’s work in Korea.

“Ah, yes. Nice to meet you.”

Eagles, wilderness, vast horizons, untamed lands. Mongolia, the land of dreams and freedom, the sovereign nation with the lowest population density on Earth.

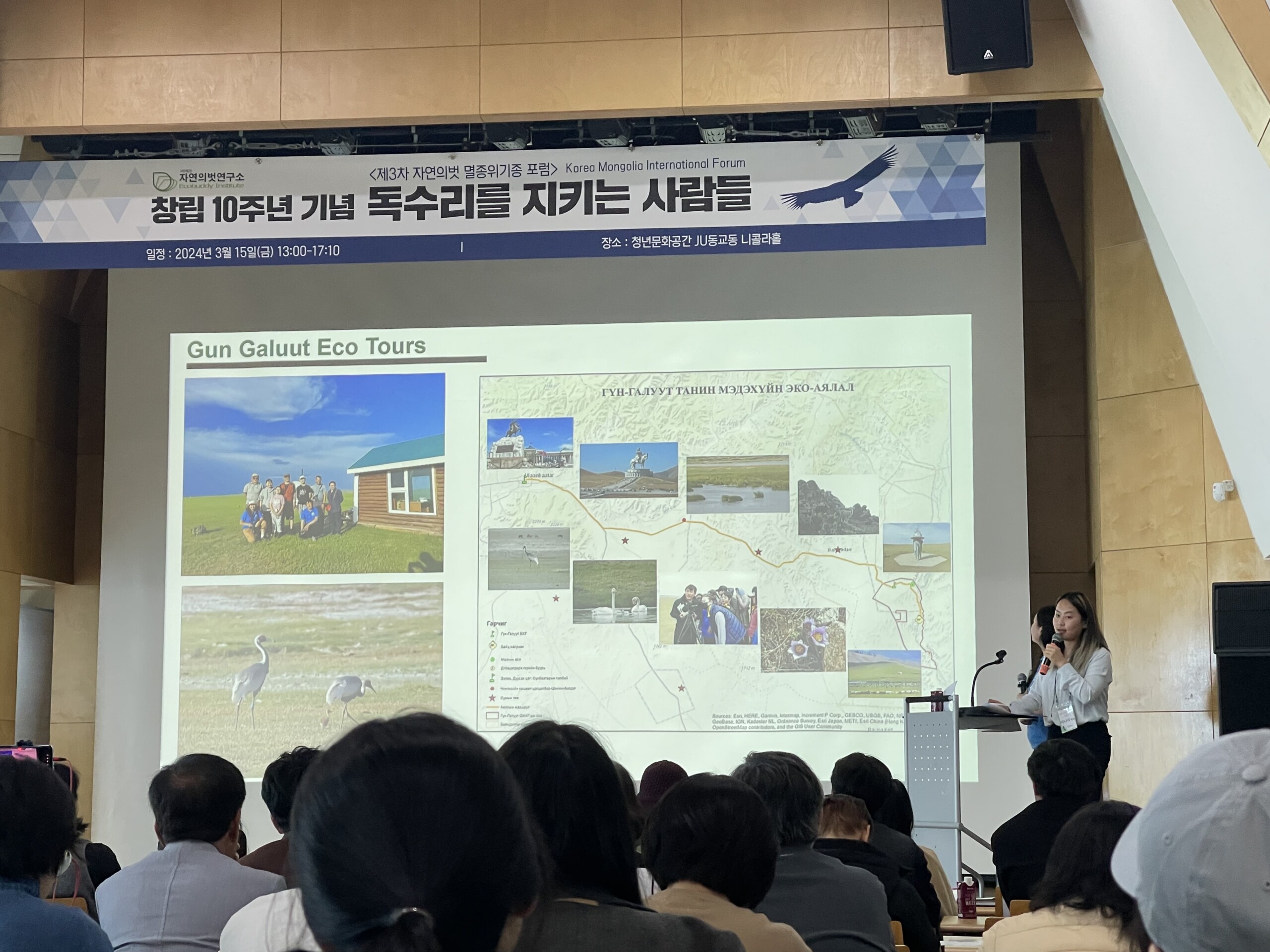

Figure 1. Author co-organizing the Mongolia-Korea Vulture Conservation Forum through her environmental organization, Zigudang (Action to Save the Earth), and inviting a leading female ornithologist © Ecobuddy).

Figure 1. Author co-organizing the Mongolia-Korea Vulture Conservation Forum through her environmental organization, Zigudang (Action to Save the Earth), and inviting a leading female ornithologist © Ecobuddy).

In Korea, I ran an environmental NGO under the name Eagle Unnie (Sister). I wanted to leave a strong impression on people through my persona, shaped by my work in Mongolia. “Eagle” and “Sister” – two words people wouldn’t normally associate with each other. The strength and bravery of the eagle have traditionally been associated with masculine figures, such as older brothers or fathers.

“Wow, Eagle Sister, I’ve always wanted to meet you. How could a woman endure a country like Mongolia?”

In South Korea, the middle-aged men I met at NGOs, birdwatching, and environmental events often spoke this way, full of admiration for me. Over time, I had become a woman of steel, earning my place in the wild under a male-dominated authority. I enjoyed the attention, the influence, and the recognition. But when I returned to the quiet of my own space, nights were filled with unease and lingering questions.

My experience in Mongolia was no different in that regard. I arrived with little to no experience or knowledge as an environmentalist and began working as an international volunteer supported by the Korean government at a bird-banding station. Obsessed with birds, I had established a nonprofit in Korea within months, balancing a day job with nights spent educating people about birds. Finally, here was a chance to handle live birds and conduct research firsthand.

Figure 2. Banding a Saker Falcon (Falco cherrug) for research purposes (after extensive training in bird handling) © MBCC.

Figure 2. Banding a Saker Falcon (Falco cherrug) for research purposes (after extensive training in bird handling) © MBCC.

Fieldwork in Mongolia begins each year around April, when the harsh winter ends and migratory birds return. But the conditions were brutal. The bird banding station, located roughly 400 km from the capital, faced unpredictable weather. One day, sandstorms raged, then suddenly froze into biting cold, with snowflakes swirling. The next day, it could be warm enough for short sleeves. Coming from soft, leisurely birdwatching experiences, my first exposure to Mongolia’s extreme wilderness came as a shock.

The environment was especially punishing for someone like me, living with a chronic illness: hyperthyroidism. The condition disrupts the immune system, has a low cure rate, and comes with severe fatigue, irregular heartbeat, and lethargy – completely disqualifying symptoms for a field researcher.

Of course, the field itself was far from easy. Working in temperatures that plunged to -4°F, along with Mongolia’s unpredictable weather, was more challenging than I had imagined.

At my first meeting with the local staff, I introduced myself and shared my health condition in Mongolian. For a moment, their expressions looked serious. I remember feeling a flicker of fear. What if this prevented me from experiencing the fieldwork I had longed for? However, the bird banding station in Mongolia struggled with a lack of staff, and fortunately, I had the chance to take part in the fieldwork.

Living with people from multiple countries also revealed cultural differences. Researchers in Mongolia often stay together in gers (Mongolian traditional dwellings) or other temporary accommodations for months or even years in the midst of the steppe. When you spend that long with people from different backgrounds, lifestyle habits, and values, it can lead to moments of discomfort.

On top of that, I felt I had a task of my own: breaking the stereotypes locals might have about Korean women. With my chronic illness added into the mix, this was unexpectedly challenging. Due to the nomadic culture, Mongolia tends to lean toward machismo. Known for their tall, strong builds, locals sometimes perceive Koreans as relatively delicate. As a result, my Mongolian colleagues often asked me, “Are you struggling?” or “Are you okay?” whenever I was in the field. Though these questions were meant kindly, reflecting their generosity and desire to take care of a “poor Korean woman,” they sometimes felt like a weight on me. It wasn’t wrong – just a subtle cultural difference – but in some ways it posed a challenge that I had to navigate.

I tried never to appear weak, always answering, “I’m fine”, and maintaining a strong outward demeanour. I carried cold medicine year-round, but never let anyone see, anxious that my health might disqualify me from field research.

Figure 3. Author and Saker Falcon, the national bird of Mongolia © Nari Lee.

Figure 3. Author and Saker Falcon, the national bird of Mongolia © Nari Lee.

Sometimes, Mongolian women tried to exclude me from chopping wood or lighting fires. “Nari, that’s men’s work”, they’d say, suggesting my boyfriend or a male colleague handle it next time. While these gestures were meant to be considerate, they felt uncomfortable to me – but I often had to accept them as part of local custom.

Other local researchers also drew clear gender boundaries during fieldwork. One woman decided to focus solely on cleaning and cooking for the season, while a man her age took full responsibility for equipment and banding. Even though they were equal researchers, it was surprising to see people limit their own opportunities based on perceived roles.

Among the international volunteers, there were subtle tensions and debates over banding experience and skill. When things got busy, the more experienced researchers usually had priority for taking bird measurements, leaving beginners with fewer hands-on opportunities. To gain experience, we often relied on the generosity of these skilled researchers.

Living through these situations brought mixed emotions. Even amid the excitement of encountering birds, coexisting and working closely with people with different values and habits wasn’t easy. It was my first experience living and working in the same space all day, and it often made me wish for shared rules that everyone could agree on.

These moments of frustration have become a new source of motivation for me. They encourage me to continue my research, which supports women in conservation in Mongolia and Korea. In both Mongolia and Korea, conservation leadership is still overwhelmingly male, and there’s very little research addressing gender inequality in this field. In Mongolia, women make up only 15% of top management positions (World Bank, 2024); in Korea, it’s just 8% (Song, 2022). Yet studies consistently show that gender diversity in conservation teams improves outcomes (Westermann et al., 2005). Despite this, women continue to be sidelined, facing pay gaps, assumptions of incompetence, and sexual harassment.

Figure 4. Author and her colleagues from the Bad Feminist group © Nari Lee.

Figure 4. Author and her colleagues from the Bad Feminist group © Nari Lee.

The journey wasn’t easy. Even finding Mongolian women willing to serve as advisors was challenging. Just speaking openly about these topics could mark them with stigma in this male-dominated culture. But one Mongolian woman reached out to me and offered to assist, saying she wanted to break the silence. She shared her own experiences of sexual harassment in the field and decided it was time to speak up.

As more women around the world share their stories, I’m determined to help build that same chorus of voices in Mongolia, Korea, and beyond. I wonder: in your own community, who’s still waiting for the chance to speak up?

If you are interested in contributing to the #BOUdiversityBlog, please get in touch with us via this form which ensures anonymity for those who seek it.

Featured image credit: CCO PD pixabay.com