LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Reuse of nests in the Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus: A behavior to save time and energy and to deter nest parasites? Mérő, T.O., Žuljević, A., Kolykhanova, O. & Lengyel, S. 2022 Ecology and Evolution doi: 10.1002/ece3.9452 VIEW

There are bird species in which nest reuse is a common phenomenon; after broods within a season or between the seasons they search for their old nests in order to raise a new clutch. This behaviour is, for example, frequent in raptors, crows and cavity nesting birds (Otterbeck et al. 2019). On the other hand waders, waterfowl or open-cup nesting passerines are known to raise their clutches in freshly build nests. However, there are rarely documented cases, where typical non nest-reusers, lay clutches in their earlier used nests (Mérő and Žuljević 2019).

While nest reuse is often considered as risky, many studies also report the benefits of this behaviour. What makes nest reuse risky? There are nest predators who are able to memorize earlier depredated nests, and they tend to revisit them from time to time, e.g., crows (Sonerud & Fjeld 1987). Reused nests may provide a reduced quality of nest construction, and being unable to hold the nest content, mostly in adverse weather circumstances (Mazgajski 2007). Another reason why reused nests may be of disadvantage is because ectoparasites of birds can accumulate during an earlier nesting cycle, mostly in case of within season nest-reuse. These ectoparasites can significantly reduce fitness of young (Rendell and Verbeek 1996). Nest reuse can also lead to later egg laying, resulting in smaller clutches and lower reproduction success (Otterbeck et al. 2019).

Let’s now see why this behaviour may be an advantage! In some species nest reuse can reduce time and effort needed for nesting site selection, and clutches can be raised earlier. This, however, may be a more usual pattern in between season nest re-users (Mazgajski 2007). Cavity nesting passerines nest two or more times within a season, this is because natural cavities are of limited availability, and it saves time and energy to stay in a used cavity (Wiebe 2011).

Figure 1 Colour ringed Great Reed Warbler male at Veliki Bački Canal near Sombor, northwestern Serbia.

The Great Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus) inhabits reed habitats, such as canals, ponds, fishponds, or shallow lakes with intermediate water depth (Mérő et al. 2018). During nesting, the species prefers reed edges adjacent to water, with taller and stronger reeds. Nesting success is strongly influenced by predation pressure, adverse weather circumstances, and brood parasitism by the Common Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) (Zölei et al. 2015). After unsuccessful nesting attempts Great Reed Warblers initiate new clutches in newly built nests, and usually do not reuse nests. There are only a very few number of cases reporting this unusual nesting behaviour for this species, for example, newly constructed nests were found under the old one suggesting nest reuse after brood parasitism (Hafstad et al. 2005, Mérő and Žuljević 2019). In our new study, we report on new unusual nesting cases in the Great Reed Warbler and provide a possible explanation to the appearance of this phenomenon.

During our fieldwork conducted on Great Reed Warbler nesting from 2008 to 2021, we observed and monitored 1607 nests. In total we found six cases of nest-reuse (including Mérő and Žuljević 2019), which was observed in only 0.4% of all nests. Here we provide details only about the cases from the aforementioned paper above.

In the first case, warblers were recorded re-using nests twice, i.e., a nest was found in a mining pond and was reused twice in the same season after unsuccessful nesting attempts. The nest was depredated twice during the egg stage. Following this, the female laid new eggs producing four fledglings. In the second case, the nest was reused after egg depredation. The reused nest was again depredated. In the third case, the female laid new eggs among the eggs that failed to hatch previously. Only one nestling hatched, that was later depredated together with the unhatched eggs.

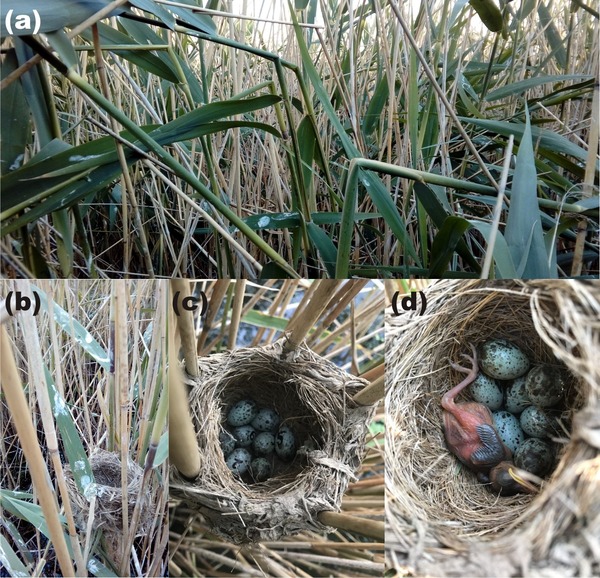

Figure 2 Reed damage (a), and nest desertion (b) due to en mass roosting of Starlings in the reed bed of the mining pond near Gakovo in 2019. Great Reed Warbler nest with initial and replacement clutch in the same nest (nest reuse) with eight eggs (c), and later with a hatched five-day-old nestling and seven unhatched eggs (d) at Veliki Bački Canal at the Fernbach farm. The nest was later depredated.

Similar to our earlier observations (Mérő and Žuljević 2019), reusing nests failed to support the predator avoidance hypothesis, concluding that nest reuse may be highly risky in open-cup nesting passerines. We believe that our observations tend to follow the time/energy saving theory (Cancellieri and Murphy 2013). We also believe that nest reuse may help in deterring brood parasites, such as Common Cuckoos, which usually lay eggs into nests at the clutch initiation stage. Because nest reuse rarely occurs in open-cup nesting passerines, we encourage experts to carefully document such cases and publish them. This will not only increase the bibliographic data of such behaviour but will increase our knowledge on the background of this phenomenon.

References

Cancellieri, S. & Murphy, M.T. 2013. Experimental examination of nest reuse by an open-cup-nesting passerine: time/energy savings or nest site shortage? Animal Behaviour 85: 1287-1294. VIEW

Hafstad, I., Stokke, B.G., Vikan, J.R., Rutila, J., Røskaft, E. & Moksnes, A. 2005. Within-year nest reuse in open-nesting, solitary breeding passerines. Ornis Novegica 28: 58-61. VIEW

Mazgajski, T.D. 2007. Effect of old nest material on nest site selection and breeding parameters in secondary hole nesters – a review. Acta Ornithologica 42: 1-14. VIEW

Mérő, T.O., Žuljević, A., Varga, K. & Lengyel, S. 2018. Reed management influences philopatry to reed habitats in the Great Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus). The Condor: Ornithological Applications 120: 94-105. VIEW

Mérő, T.O. & Žuljević, A. 2019. Unusual nests in the Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus: reuse of nests in the same season and unusual forms of nest construction. Ardea 107: 93-96. VIEW

Otterbeck, A., Selås, V., Nielsen, T.J., Roualet, É. & Lindén, A. 2019. The paradox of nest reuse: early breeding benefits reproduction, but nest reuse increases nest predation risk. Oecologia 190: 559-568. VIEW

Rendell, W.B. & Verbeek, N.A.M. 1996. Are avian ectoparasites more numerous in nest boxes with old nest materials? Canadian Journal of Zoology 74: 1819-1825. VIEW

Sonerud, G.A. & Fjeld, P.E. 1987. Long-term memory in egg predators: an experiment with a hooded crow. Ornis Scandinavica 18: 323-325. VIEW

Wiebe, K. 2011. Nest sites as limiting resources for cavity-nesting birds in mature forest ecosystems: a review of the evidence. Journal of Field Ornithology 82: 239-248. VIEW

Zölei, A., Bán, M. & Moskát, C. 2015. No change in common cuckoo Cuculus canorus parasitism and great reed warblers’ Acrocephalus arundinaceus egg rejection after seven decades. Journal of Avian Biology 46: 570-576. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Zeynel Cebeci CC BY SA 4.0 Wikimedia Commons.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.