Over the last decade, being able to deploy small tracking devices on seabirds has provided us with astonishing insights into their lives offshore. Some of the recent insights take us to the west coast of Ireland where Manx Shearwaters have broken records and prove that location matters.

Over the last decade, being able to deploy small tracking devices on seabirds has provided us with astonishing insights into their lives offshore. Some of the recent insights take us to the west coast of Ireland where Manx Shearwaters have broken records and prove that location matters.

There is something very fascinating about the elusiveness of seabirds. While the buzzing noise of a seabird colony can be heard (and smelled) from far away, they completely disappear from our senses once they have left shore to only magically return later with food to feed their chicks.

Some seabirds, such as Manx Shearwaters, are even more mysterious and experiencing their colonies on remote and often inhabited islands can turn the experience into a real adventure requiring both a compulsory bumpy boat ride and a good headlight as birds only return to their nest burrows at night.

Studying Manx Shearwaters in Ireland

Studying Manx Shearwaters means many hours of night-time fieldwork on one’s knees with arms down muddy burrows feeling for fluffy chicks and their feisty parents. Even usually simple tasks such as defining the size of a colony can be challenging (Arneill et al 2020).

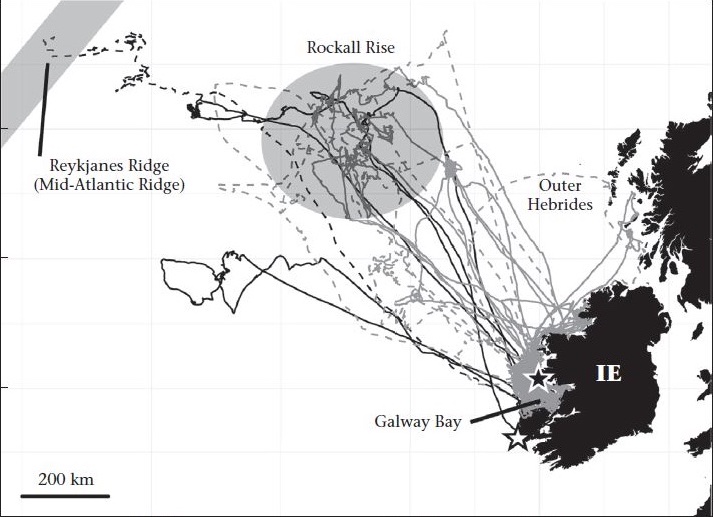

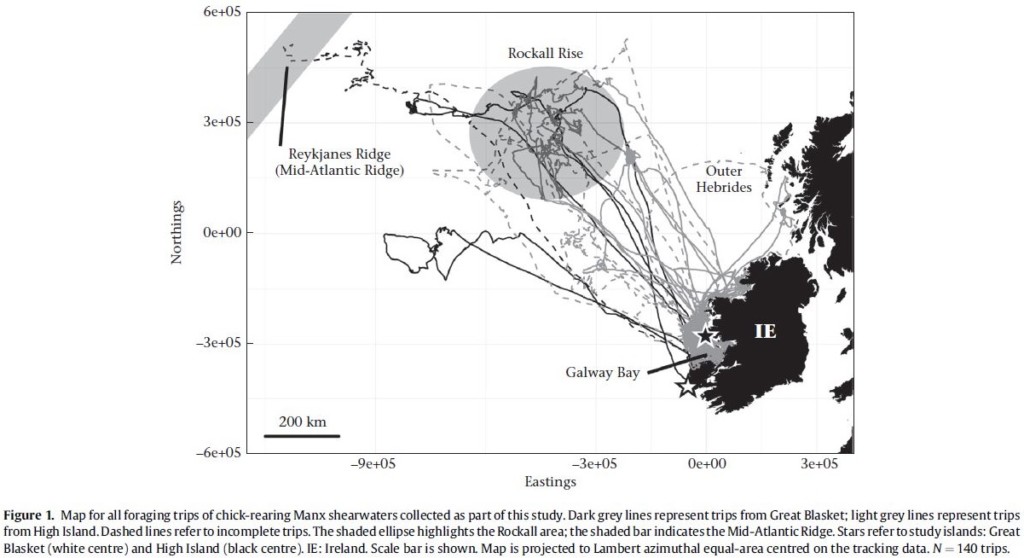

Until recently most of this work was mainly concentrated on few long-term studies within some of the biggest colonies located in and around the Irish Sea. A study led by researchers at University College Cork expanded their usual study area with the aim understand where, and particularly why, Manx Shearwaters from the west coast of Ireland go to where they go at sea, and how this might differ from birds breeding elsewhere. Over three years GPS tracking and monitoring data were collected and analysed with the results published in multiple scientific publications over the last year and include some exciting findings.

Breaking records

Compared to their counterparts on Welsh islands, Manx Shearwaters breeding on Irish islands regularly travelled enormous distances offshore up to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge before returning to their single chick. The 1120 mile (1170 km) journey is equivalent to the distance from London to Rome and about five times as far as the expected regular breeding range for the species (Wischnewski et al 2019). These long trips set the record for the longest distance travelled by an actively and successfully breeding seabird in the northern hemisphere and came as a huge surprise as these trips could last up to 11 days.

Bad parenting?

Compared to other cliff-nesting seabirds, Manx Shearwater chicks are mostly safe from predators when left alone in their burrows and the second parent will usually still take care of the chick even when other parent is away foraging. The study also showed that Irish Manx Shearwaters, like numerous other seabirds species, alternate between short trips aimed at quickly collecting as much food as possible relatively close to the colony to bring it back to their hungry chick, and long trips during which birds restore their own energy reserves as well as bring back food for their chick. Therefore, parents would only leave on long foraging trips if their chick was in good condition and they would themselves would return in better condition (Wischnewski et al 2019).

Why travel further than necessary?

This is a difficult question and finding a clear answer is not easy. There might be less competition for food, food resources might be qualitatively and quantitatively better, or the reason might not be linked to food at all. The newest publication of the study indicates that Irish Manx Shearwaters change their behaviour from travelling to foraging in highly productive, potentially food rich areas, suggesting that at least most of their trips are indeed foraging trips aimed to find food (Kane et al 2020). However, the relationship was less clear for offshore trips, maintaining their mystery, at least for now.

Seabirds are one of the most threatened groups of animals on the planet and understanding where they go at sea, and why, is critical to protect them from ever increasing anthropogenic pressures such as climate change, overfishing and energy developments. To complicate things, this tracking study showed that where and how far seabirds go at sea very much depends on where their colonies are located. We cannot simply presume it is the same everywhere but need targeted local studies when developing conservation plans.

Seabirds are one of the most threatened groups of animals on the planet and understanding where they go at sea, and why, is critical to protect them from ever increasing anthropogenic pressures such as climate change, overfishing and energy developments. To complicate things, this tracking study showed that where and how far seabirds go at sea very much depends on where their colonies are located. We cannot simply presume it is the same everywhere but need targeted local studies when developing conservation plans.

References

Arneill, G.E., Critchley, E.J., Wischnewski, S., Jessopp, M.J. and Quinn, J.L.. 2020. Acoustic activity across a seabird colony reflects patterns of within‐colony flight rather than nest density. IBIS 162: 416-428. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12740. View

Kane, A., Pirotta, E., Wischnewski, S., Critchley, E.J., Bennison, A., Jessopp, M. & Quinn, J.L. 2020. Spatio-temporal patterns of foraging behaviour in a wide-ranging seabird reveal the role of primary productivity in locating prey. MEPS 646:175-188. DOI: 10.3354/meps13386 View

Wischnewski, S., Arneill, G.E., Bennison, A.W., Dillane, E., Poupart, T.A., Hinde, C.A., Jessopp, M.J. and Quinn, J.L.. 2019. Variation in foraging strategies over a large spatial scale reduces parent–offspring conflict in Manx shearwaters. Animal Behaviour 151: 165-176. DOI: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.03.014. View

Image Credits</strong >

Manx Shearwater in burrow, island landscape and fieldworkers © Saskia Wischnewski

Manx Shearwater in flight – Matt Witt CC BY SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.