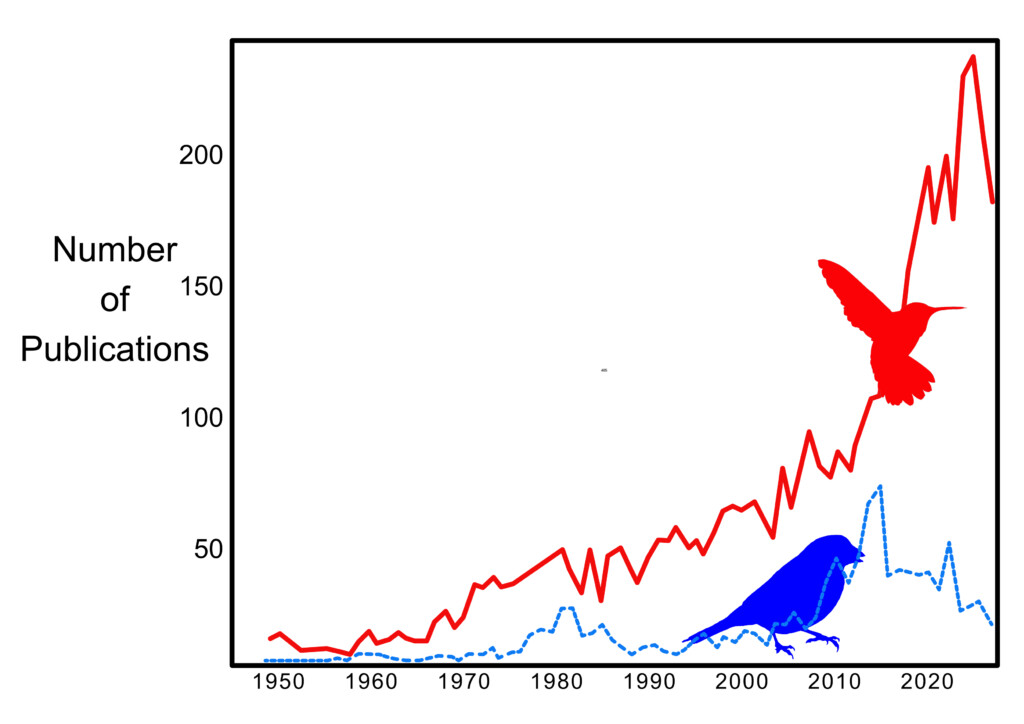

Shortly after I arrived at McGill University in the fall of 1973, my PhD supervisor asked if I wanted to accompany him to the Galápagos to study the foraging ecology of Darwin’s Finches. “Nah,” I replied, “they look rather boring to me, and haven’t they been studied to death by Lack, Bowman and others?” Was I ever wrong, as that early expedition led to a half century of ground-breaking research, celebrated in myriad papers and several books. I played a small part in recruiting a few outstanding graduate students to that project, but I have never regretted my decision, and did not visit the Galápagos until 2018. Instead, I went to Mexico to study hummingbirds, inspired by the ongoing, exciting research of Larry Wolf, Reed Hainsworth, Gary Stiles, Rob Colwell, and Peter Feinsinger. Hummingbirds (and for that matter Darwin’s Finches) still fascinate me.

Hummingbirds also enchanted the earliest European visitors to the Americas. Spanish explorers in the 16th century certainly encountered many hummingbirds on Caribbean islands, and throughout Central and South America. It should come as no surprise that Europeans were fascinated by hummingbirds as none of the European birds that they knew were so small, could hover and fly backwards on a blur of wingbeats, seemed to live on floral nectar, and displayed such a marvellous array of iridescent plumage colours. Some early explorers even wondered if they were really birds.

Those early Spanish explorers were the first to write about hummingbirds, calling them ‘pajaro-musca’ (bird-fly), ‘pajaro-mosquito’ (little bird-fly), ‘joyas voladoras’ (flying jewels), and ‘picaflores’ (flower-stingers). More recently they have been called ‘chuparosa’ (rose sucker) and ‘chupamirto’ (myrtle sucker) in Spanish, names still in common use in Mexico.

The early French explorers to the Americas called hummingbirds ‘oiseau de fleur’ (flower-bird), as well as ’oiseau-mouche‘ (bird-fly) and ‘souce-fleur’ (flower sucker), possibly simply translating the Spanish. In 1640, Jacques Bouton, writing about the wildlife of Martinique, said that “in this country, as in Canada, there are certain small birds with very beautiful plumage that live on flowers as well as bees: we call them colibry, which is the word used by the natives, meaning bird, and which we have adopted specifically for this one; some are brought to France.” (English translation from the French in Bouton 1640:73), Here the ‘natives’ were presumably the indigenous Taino. Then, in his 1863 Dictionnaire de la langue française, Émile Littré wrote this as ‘colibri’” a name later adopted by zoologists as one of the hummingbird genera. Colibri is what hummingbirds are now called in France though in the Americas ‘oisieau-mouche‘ is more commonly heard in French Canada, and ‘suce-fleur‘ in the cajun patois of Louisiana

The first reference to hummingbirds in English was probably when William Wood wrote in 1634 that ‘The Humbird is one of the wonders of the Countrey, being no bigger than a Hornet, yet hath all the dimensions of a Bird, as bill and wings, with quils, Spider-like legges, small clawes: For colour, she is as glorious as the Raine-bow; as shee flies, shee makes a little humming noise like a Humble-bee: wherefore she is called the Humbird.’ (Wood 1634:28). This is an interesting departure from the French and Spanish names that all referred to their small size or their affinity for flowers, rather than the sounds made by their whirring wings.

Then, in 1637, Thomas Morton wrote that “There is a curious bird to see to, called a hunning bird, no bigger then a great Beetle; that out of question lives upon the Bee, which hee eateth and catcheth amongst Flowers: For it is his Custome to frequent those places. Flowers hee cannot feed upon by reason of his sharp bill, which is like the poynt of a Spannish needle, but shorte. His fethers have a glosse like silke, and, as hee stirres, they shew to be of a chaingable coloure: and has bin, and is, admired for shape, coloure and size.” (Morton 1637:199).

And by 1672, John Josselyn [1638-1675] seemed to know the bird well, though he thought that they slept through the winter and had a clutch of more than two eggs: “The Humming Bird, the least of all Birds, little bigger than a Dor [dung beetle], of variable glittering Colours, they feed upon Honey, which they suck out of Blossoms and Flowers with their long Needle-like Bills; they sleep all Winter, and are not to be seen till the Spring, at which time they breed in little Nests, made up like a bottom of soft, Silk-like matter, their Eggs no bigger than a white Pease, they hatch three or four at a time, and are proper to this Country.” (Josselyn 1672:6-7).

John Gould, in his magnificent Monograph of the Trochilidae (1861-1887), is largely responsible for many of the more imaginative English names that we still use: brilliant, comet, coquette, emerald, firecrown. wood-nymph, golden-throat, helmet-crest, hermit, inca, lance-bill, mountaineer, plumeleteer, puff-leg, raquet-tail, sabre-wing, sapphire, sickle-bill, snowcap, star-frontlet, star-throat, sunbeam, sylph, thorn-bill, thorn-tail, topaz, train-bearer, violet-ear, and white-tip. He called them the ‘gems of creation’, often giving them the names of precious stones.

Early attempts to take live hummingbirds back to Europe were unsuccessful until Samuel de Champlain apparently took a living Ruby-throated Hummingbird back to the royal court in France in 1607 (Fischer 2009). By the early 1800s, a method of bringing live hummingbirds to Europe had been perfected, as John Gould describes: “The specimens I brought alive to this country were as docile and fearless as a great moth or any other insect would be under similar treatment. The little cage in which they lived was twelve inches long, by seven inches wide, and eight inches high. In this was placed a diminutive twig of a tree, and, suspended to the side, a glass phial which I daily supplied with saccharine matter in the form of sugar or honey and water, with the addition of the yelk of an unboiled egg. Upon this food they appeared to thrive and be happy during the voyage… ” Gould (1849-67)

Collections of both living hummingbirds and preserved specimens were wildly popular in Europe in the 19th century. John Gould, for example, was able to make 24 cases of mounted hummingbirds from his own collections to display in the Hummingbird House at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Ever the entrepreneur, Gould undoubtedly saw that exhibition as an excellent advertisement for Monograph of the Trochilidae, with exquisite illustrations sometimes using gold and silver leaf to mimic iridescence. Not to be outdone, Martial Étienne Mulsant and Édouard Verreaux published their own monograph of hummingbirds (Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux-Mouches, ou Colibris constituant la famille des Trochilïdes) in 1874, beautifully illustrated by Louis Victor Bevalet.

After that flurry of 19th century interest, little was published on hummingbirds, except to describe new species, for several decades. Then in 1960, Crawford Greenewalt published a large format book of astounding—in those days—colour photographs of hummingbirds in flight. Working with engineers at Dupont, where he was president, Greenwalt developed both strobe lighting and cameras capable of taking photos that froze the birds blurring wings as they hovered. In addition to the marvellous photography, Greenewalt developed models for hummingbird iridescence, flight, and energetics. Alden Miller said in his 1961 review of that book in The Condor that it “…revealed for him esthetic and scientific values which he could never have attained fully from watching the highly active birds or from the study of the specimens…” I expect that Greenewalt’s book inspired many to start studying the ecology and behaviour of hummingbirds in the field.

There’s no denying that the work of Peter and Rosemary Grant on Darwin’s Finches brilliantly explored the action of natural selection in the wild. I would argue, though, that the study of hummingbirds, which also began to blossom a half century ago, has continued to inspire interesting work on all aspects of their behaviour, ecology, physiology, anatomy, and evolution.

Further Reading

Bouton, J. (1640) Relation de l’establissement des François depuis l’an 1635 en l’isle de la Martinique, l’une des Antilles de l’Amérique, des moeurs des sauvages, de la situation et des autres singularitez de l’île. Sebastien Cramoisy, Paris. VIEW

Fischer, D.H. (2009) Champlain’s Dream. Simon and Schuster. VIEW

Gould, J. (1849-1867) A monograph of the Trochilidæ, or family of humming-birds. Vols 1-5 and supplement. Published by the author, London. VIEW

Greenewalt, C.H. (1960) Hummingbirds. Doubleday, New York.

Josselyn, J. (1672) New-Englands Rarities Discovered: In Birds, Beasts, Fishes, Serpents, and Plants of that Country. Together with The Physical and Chyrurgical Remedies wherewith the Natives constantly use to Cure their Distempers, Wounds, and Sores. Also a perfect Description of an Indian Squa, in all her Bravery; with a Poem not improperly conferr’d upon her. Lastly a Chronological Table of the most remarkable Passages in that Country amongst the English. G. Widdowes, London.

VIEW

Morton, T. (1637) New English Canaan or New Canaan; Containing an Abstract of New England, Composed in three Bookes. J. F. Stam, Amsterdam. VIEW

Wood, W. 1634) New Englands Prospect. John Bellamie, London. VIEW

Image Credits

Book covers: author’s photographs and publisher’s websites

Magnificent spatuletail: Gould (16 ) in the public domain

Graph; data from Web of Science searching for all publications from 1950-2025 using the keywords Trochilidae and hummingbird for the red line, and Darwin’s Finch, Galapagos Finch and Geospiza for the blue one.