LINKED PAPER

Differential impact of anthropogenic noise during the acoustic development of begging calls in Blue Tits (Cyanistes caeruleus). Sierro, J., de Kort, S. R., Hartley, I. R. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13299. VIEW

Humans have had massive impacts on environments worldwide, and one of the most common ways we have modified habitats is by making them noisier. As acoustic communication is often very important to birds, the disruption of this communication by anthropogenic noise may have negative effects on various aspects of avian success and survival. One example of acoustic communication is nestling begging calls, but as these calls are not only different between species but also change during nestling development, understanding the impacts of anthropogenic noise on parent-offspring communication can be difficult.

In a recent study in Ibis, Javier Sierro and colleagues investigated changes in the acoustic structure of begging calls of nestling Eurasian Blue Tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) through development, to explore how and when increased anthropogenic noise might have the greatest impact on parent-offspring communication at the nest.

Acoustic structure of sound

The use of begging calls by nestlings of altricial birds is widespread, and they are thought to be an honest indicator of need which parents use to adjust provisioning rates (Marques et al. 2009, García-Campa et al. 2021). Vocalisations travel further than visual signals, with the acoustic structure of a sound determining not only its transmission distance but also how easy it to locate its source. The researchers measured the relative amplitude, the spectral characteristics, and the tonality (or noisiness) of nestling Blue Tit begging calls, and aimed to set specific predictions for when anthropogenic noise will have a stronger masking effect to identify vulnerable phases during the reproductive cycle.

Figure 1. Spectrogram of examples of begging calls of nestling Blue Tits from the same brood during development (a) with the associated amplitude waveform (b).

Vulnerable points in development

The results showed that the acoustic properties of nestling Blue Tit begging calls changed significantly and non-linearly through development, with the researchers identifying three phases. In the first phase, from one to about five days post-hatching, begging calls were narrow-band sounds (i.e. pure tones) of very low amplitude and relatively low frequency. In the second phase, from about 5 to 12 days post-hatching, calls were louder tonal sounds with higher frequency and wider frequency modulations. In the third phase, from about 12 to 16 days post-hatching, the calls transformed into loud, hiss-like sounds of broadband frequency.

When considering road traffic noise, which is generally concentrated at lower frequencies (Gill et al. 2014, Sierro et al. 2017), the researchers hypothesised that nestling Blue Tit begging calls might be particularly vulnerable to interference at two points during development. The first vulnerable point is during the first growth phase, when the low amplitude and relatively low frequency of begging calls make them easily masked by anthropogenic noise. The second vulnerable point is during the transition between the second and third phases, when begging calls change from being highly tonal sounds to being chaotic, noisy, hiss-like sounds which degrade faster under noisy conditions.

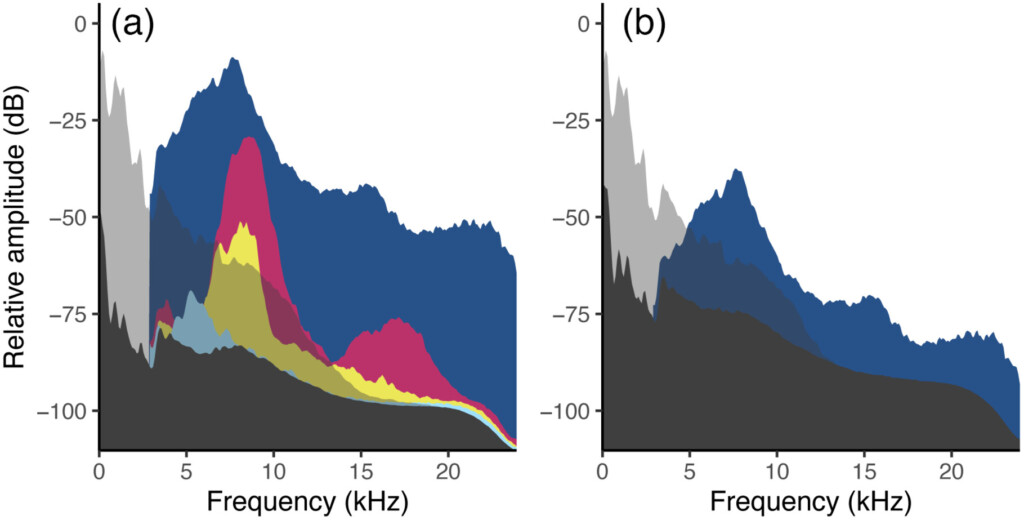

Figure 2. Power-spectrum of begging calls of nestling Blue Tits at different age classes (light blue, yellow, pink and dark blue) recorded in an urban woodland with low ambient noise, overlaid with the ambient noise profile (black) recorded in a rural woodland with natural ambient noise and the motorway noise profile (grey) recorded in an empty nestbox near the motorway with identical recording equipment and settings. We show only four age classes that split the entire nestling period into equal-length intervals, day 1 (light blue), day 5 (yellow), day 10 (pink) and day 15 (dark blue). (a) Power-spectrum of each sound as originally recorded, normalized for the maximum amplitude with the current recording settings and transformed into dB (logarithmic scale). (b) Estimated signal-to-noise ratio at 1m distance from the nestbox (see Methods for details).

Based on the outcomes of this study, the researchers predict that in areas with high levels of anthropogenic noise, there could be an issue at the two vulnerable points identified whereby parents are unable to assess begging calls adequately, resulting in a mismatch between provisioning rates and offspring need. While this mismatch could lead to reduced growth rate at these vulnerable points, it is possible that parents can compensate for this if communication is efficient at other points of development. This could explain why other studies of begging calls, which often only focus on a certain stage of nestling development, have found disruption of parent-offspring communication but no effect on nestling mass at the end of the nestling period (e.g. Leonard et al. 2015). It is also possible that, while nestling growth rate is not affected, provisioning parents could suffer costs under noisy conditions which may compromise their own survival (Santos & Nakagawa 2012).

In noisy conditions, nestlings may be able to modify their calls to transmit better, but as the variation in amplitude and frequency of sounds is limited by body size and may incur energetic costs the ability to do this may vary through development.

While the developmental changes of begging calls in Blue Tits described in this study are almost identical to those described for Tree Swallows (Leonard & Horn 2008), they differ from other species, and further research to describe acoustic development of begging calls in a wider range of species would help to increase understanding of acoustic vulnerable points which can then be used to inform mitigation strategies.

References

García-Campa, J., Müller, W., Hernández-Correas, E. & Morales, J. (2021). The early maternal environment shapes the parental response to offspring UV ornamentation. Scientific Reports 11: 20808. VIEW

Gill, S.A., Job, J.R., Myers, K., Naghshineh, K. & Vonhof, M.J. (2014). Toward a broader characterization of anthropogenic noise and its effects on wildlife. Behavioural Ecology 26: 328–333. VIEW

Leonard, M.L. & Horn, A.G. (2008). Does ambient noise affect growth and begging call structure in nestling birds? Behavioural Ecology 19: 502–507. VIEW

Leonard, M.L., Horn, A.G., Oswald, K.N. & McIntyre, E. (2015). Effect of ambient noise on parent–offspring interactions in tree swallows. Animal Behaviour 109: 1–7. VIEW

Marques, P.A., Vicente, L. & Márquez, R. (2009). Nestling begging call structure and bout variation honestly signal need but not condition in Spanish sparrows. Zoological Studies 48: 587–595. VIEW

Santos, E. & Nakagawa, S. (2012). The costs of parental care: A meta-analysis of the trade-off between parental effort and survival in birds. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 25: 1911–1917. VIEW

Sierro, J., Schloesing, E., Pavón, I. & Gil, D. (2017). European blackbirds exposed to aircraft noise advance their chorus, modify their song and spend more time singing. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 5: 68. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Young Blue Tit (Cyanistes caeruleus) | N p holmes | CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here