LINKED PAPER

Nest reliefs in a cryptically incubating shorebird are quick, but vocal. Bulla, M., Muck, C., Tritscher, D., Kempenaers, B. 2022. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13069. VIEW

In many relationships and interactions, communication is key. An excellent demonstration of this in birds is during biparental care, when parents must coordinate their behaviour to successfully rear offspring. For example, during biparental incubation only one parent can care for eggs at one time, but continuous nest attendance increases reproductive success. Effective communication is vital to coordinate a pair’s behaviour, and where opportunities to communicate are scarce, such as when the off-duty parent forages far away and the pair can only communicate during the brief period of exchange at the nest, this may have led to the evolution of elaborate nest relief rituals (Glutz von Blotzheim, 1999). However, little is known about how such conspicuous rituals might work in cryptically incubating species where discretion around the nest is important.

In a 2022 study in Ibis, Martin Bulla and colleagues investigated nest relief behaviour during incubation in the Semipalmated Sandpiper (Calidris pusilla), an Arctic-breeding shorebird with passive nest defence, to determine whether nest relief rituals evolved in such species that rely on crypsis to avoid predation.

Cryptically incubating Semipalmated Sandpipers

Semipalmated Sandpipers are cryptic during incubation. The cryptically coloured parents often weave a ‘roof’ over the next cup and adapt their preen oil composition and behaviour to limit detection by humans and potential predators (Ashkenazie & Safriel 1979, Bulla et al. 2016, Reneerkens et al. 2005). Off-duty parents forage up to 2km from the nest (Bulla et al. 2015). The researchers used a continuous monitoring system to investigate if the incubating parent actively initiates the nest relief by calling or flying off the nest, quantitatively and qualitatively described the nest relief process, and explored whether the nest relief process duration and vocalisations provided information about parental coordination.

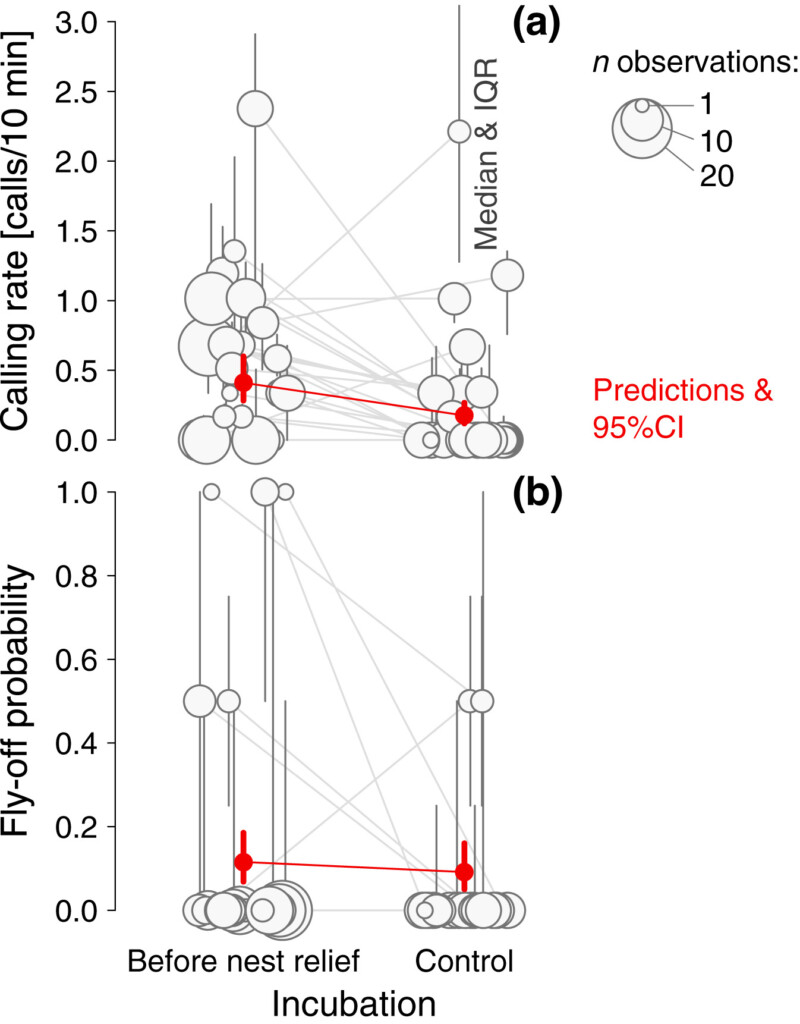

Figure 1. Calling rate (a) and the probability of flying off the nest (b) by the incubating parent before arrival of its off-duty partner and during other times of incubation (control). Circles with bars indicate median and interquartile range for each of 29 nests. Circle size indicates the number of observations. Grey lines connect observations from the same nest. Red points with bars indicate model predictions with 95% CI based on the joint posterior distribution of 5000 simulated values generated from the model output by the sim function in R (Gelman & Su 2020), while keeping the other predictors constant (n = 125 before-arrival and n = 114 control observations).

Nest relief rituals

The researchers found that the general nest relief procedure in this species was brief, but vocal. Some calls made during the nest reliefs could potentially be audible up to 155 m away (Bulla et al. 2015). While such loud vocalisations are surprising in a cryptically incubating species, the nest relief period is likely the only opportunity for parents to communicate and synchronise parental duties, with better coordination increasing reproductive success.

In the period before the off-duty parent arrived at the nest the incubating parent called more often than otherwise during incubation, which may indicate that they wanted to leave and were calling out to their partner, despite them often being out of hearing of the nest. Several results indicated that the incubating parent waited for its partner to return before leaving the nest, provided its energy stores allowed it to stay (Bulla et al. 2015), which is supported by previous findings in similar species.

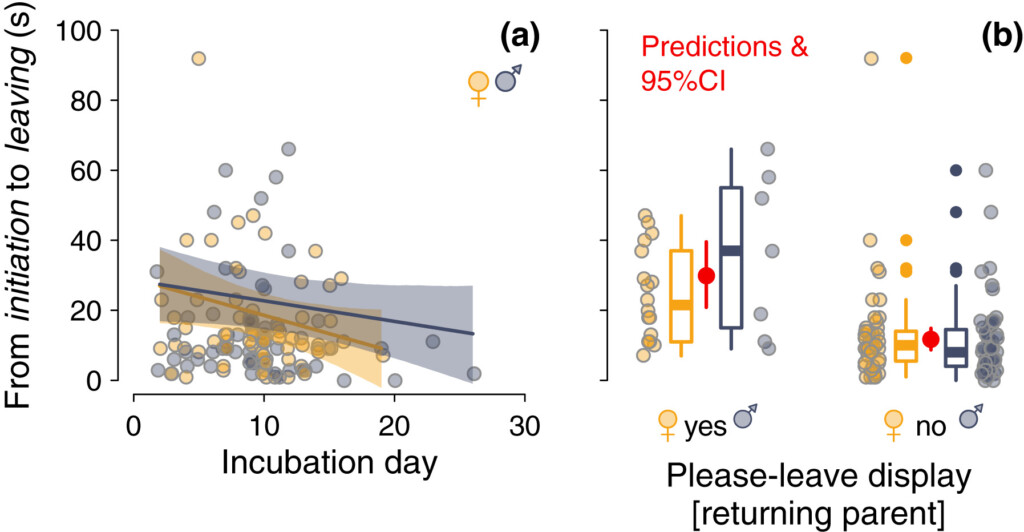

Nest reliefs (exchanges where the incubating parent left only after its returning partner initiated the exchange) became faster over the incubation period, suggesting improved coordination between the parents and less time spent with both of them at the nest, although, contrary to expectation, vocalisations did not decrease in intensity during this time.

Figure 2. Period between nest relief initiation by the returning parent and incubating parent leaving the nest in relation to the progress of the incubation period (a) and the occurrence of the please-leave display.

The findings included evidence that calls may convey information about incubation bout length. When the returning parent initiated the nest relief with a call and the incubating parent replied, the following incubation bout of the returning parent was 1-4 h longer than when there was no reply. The researchers hypothesise that the reply is a signal that the incubating parent needs a longer than normal stay off the nest. This could be tested in future studies by assessing the condition of the relieved parent and/or by experimentally manipulating the condition and analysing the effect on reply probability. Also, in females only, the calling intensity of the returning parent at the beginning of its incubation bout positively correlated with the length of the bout, but the biological relevance of this requires further study.

Overall, the results of this study expand our limited knowledge of vocalisations during biparental care, but further work is needed to improve our understanding of the role of vocalisations in the coordination and synchronisation of parental duties, and the links to parental investment.

References

Ashkenazie, S. & Safriel, U.N. (1979). Breeding cycle and behavior of the Semipalmated Sandpiper at Barrow, Alaska. Auk 96: 56–67. VIEW

Bulla, M., Stich, E., Valcu, M. & Kempenaers, B. (2015). Off-nest behaviour in a biparentally incubating shorebird varies with sex, time of day and weather. Ibis 157: 575–589. VIEW

BBulla, M., Valcu, M., Dokter, A.M., Dondua, A.G., Kosztolányi, A., Rutten, A.L., Helm, B., Sandercock, B.K., Casler, B., Ens, B.J., Spiegel, C.S., Hassell, C.J., Küpper, C., Minton, C., Burgas, D., Lank, D.B., Payer, D.C., Loktionov, E.Y., Nol, E., Kwon, E., Smith, F., Gates, H.R., Vitnerová, H., Prüter, H., Johnson, J.A., St Clair, J.J.H., Lamarre, J.-F., Rausch, J., Reneerkens, J., Conklin, J.R., Burger, J., Liebezeit, J., Bêty, J., Coleman, J.T., Figuerola, J., Hooijmeijer, J.C.E.W., Alves, J.A., Smith, J.A.M., Weidinger, K., Koivula, K., Gosbell, K., Exo, K.-M., Niles, L., Koloski, L., McKinnon, L., Praus, L., Klaassen, M., Giroux, M.-A., Sládeček, M., Boldenow, M.L., Goldstein, M.I., Šálek, M., Senner, N., Rönkä, N., Lecomte, N., Gilg, O., Vincze, O., Johnson, O.W., Smith, P.A., Woodard, P.F., Tomkovich, P.S., Battley, P.F., Bentzen, R., Lanctot, R.B., Porter, R., Saalfeld, S.T., Freeman, S., Brown, S.C., Yezerinac, S., Székely, T., Montalvo, T., Piersma, T., Loverti, V., Pakanen, V.-M., Tijsen, W. & Kempenaers, B. (2016). Unexpected diversity in socially synchronized rhythms of shorebirds. Nature 540: 109–113. VIEW

& (2020). arm: Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. R package version 1.11-2. VIEW

Glutz von Blotzheim, U.N. (ed) (1999). Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas. 3rd ed. Wiesbaden: AULA-Verlag.

Reneerkens, J., Piersma, T. & Sinninghe Damsté, J.S. (2005). Switch to diester preen waxes may reduce avian nest predation by mammalian predators using olfactory cues. Journal of Experimental Biology 208: 4199–4202. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Semipalmated Sandpiper (Calidris pusilla) | Fyn Kynd | CC BY 2.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here