LINKED PAPER

Expert knowledge assessment of threats and conservation strategies for breeding Hen Harrier and Short-eared Owl across Europe. Fernández-Bellon, D., Lusby, J., Bos, J., Schaub, T., McCarthy, A., Caravaggi, A. Irwin, S. & O’Halloran, J. 2020. Bird Conservation International. DOI: 10.1017/S0959270920000349. VIEW

As birds of prey go, Hen Harriers (Circus cyaneus) get plenty of media attention. Sadly, this is usually for all the wrong reasons, as the species is often the target of illegal poisoning and shooting in the UK’s grouse moors (Murgatroyd et al 2019). Yet UK Hen Harriers account for just 4-8% of the species’ European population. So how are other hen harrier populations faring across Europe? Do they face the same threats? How do we protect the entire European population?

The case of Hen Harriers exemplifies bird of prey research and conservation in Europe. A lot of effort goes into studying and monitoring different species across the continent, and although crucial, this work often has a regional focus, despite evidence that many European bird of prey populations are ecologically connected. What is more, the results from these projects are often buried in the grey literature (e.g. national survey reports), making them hard to access or to apply to other populations.

In March 2019, the first International Hen Harrier and Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus) meeting was held in the Netherlands. We used this opportunity to bring together the knowledge of European experts working on these two species. Hen Harriers and Short-eared Owls have more in common than may be apparent at first sight. They have overlapping European distributions (and outside of Eurasia, Short-eared Owl populations overlap with Hen Harrier sister species in North and South America). Both species nest on the ground in a variety of open habitats and both depend on birds and small mammals for food. Though previously abundant, Hen Harriers and Short-eared Owls have suffered declines in recent decades and are now of conservation concern across Europe. Indeed, the majority of experts we contacted indicated that their study populations were in decline (70% of Hen Harrier and 58% of Short-eared Owl populations covered by our study).

Figure 1 Hen Harriers (left) and Short-eared Owls (right) share many ecological characteristics, including distribution, nesting ecology, foraging habitats, and prey © Àlex Mascarell

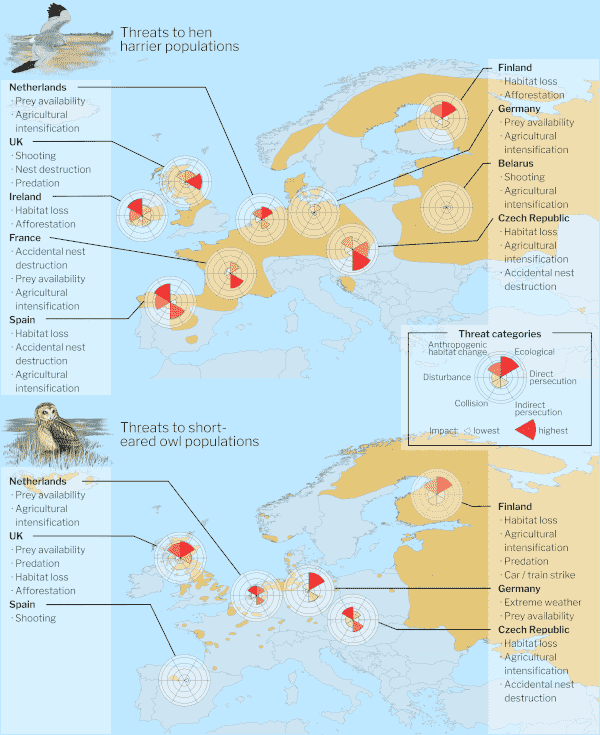

We asked experts to rate the importance of different threats to breeding Hen Harries and Short-eared Owls in their areas. Their answers suggest overlaps between the threats faced by both species, including ecological factors (such as predation, extreme weather, or prey availability), changes in land use (like habitat loss or agricultural intensification), and accidental nest destruction by humans. The similarities in threats across different areas are suggestive of the potential for joint, international conservation actions that can benefit both Hen Harriers and Short-eared Owls throughout Europe. Despite these broad similarities, some threats are more region- or species-specific. For example, while in the UK illegal killing is a major threat to Hen Harriers, neighbouring Irish Hen Harrier populations are perceived to be heavily affected by habitat loss due to widespread plantation of commercial forests. This underlines the value of current studies at a national level, which can help tailor any Europe-wide conservation strategies to also account for country-specific threats.

Figure 2 Threats to breeding Hen Harriers and Short-eared Owls across Europe. Circle sections indicate the estimated impact of each threat category (see legend) and lists indicate specific threats considered most important by experts consulted in each country. Click to view larger. Breeding distribution maps based on BirdLife International and HBW (2018), bird artwork © Àlex Mascarell

Figure 2 Threats to breeding Hen Harriers and Short-eared Owls across Europe. Circle sections indicate the estimated impact of each threat category (see legend) and lists indicate specific threats considered most important by experts consulted in each country. Click to view larger. Breeding distribution maps based on BirdLife International and HBW (2018), bird artwork © Àlex Mascarell

When experts rated various conservation strategies for breeding Hen Harriers and Short-eared Owls, they indicated that protected areas such as national parks, nature reserves, and SPA’s (special protection areas designated for these species) were the most commonly implemented. However, protected areas were rated as having intermediate or low effectiveness. The most effective conservation strategies were those relating to management of habitats (nesting and foraging) and of species (nest protection and predator control). This suggests that protected areas on their own are not enough to save these birds. These perceptions can be better understood in the wider context of the much-debated contribution of protected areas towards biodiversity conservation. These areas are often protected on paper, but not in practice, or are designated after significant habitat degradation has already occurred. Our work suggests that protected areas need to be combined with proactive conservation actions (e.g. habitat enhancement and restoration, protection of nests from predators and human persecution) to be truly effective for species conservation. These findings underline the importance of not just implementing conservation actions, but also evaluating whether they work or not. Effective conservation requires designing strategies with clear targets that can be subjected to continued assessment and amended if necessary.

Figure 3 European Hen Harrier populations are highly connected, so effective conservation requires international approaches © Mike Brown

Figure 3 European Hen Harrier populations are highly connected, so effective conservation requires international approaches © Mike Brown

So, what lies ahead for these two birds of prey? For Hen Harriers, it is time to develop a Europe-wide action plan to protect the species. This should aim to address threats that are widespread and common to the different European populations, but also make space for solving region-specific problems. In light of their continued and widespread decline, it may be necessary for countries to upgrade the species’ national conservation status, and to re-assess its IUCN global conservation status. For Short-eared Owls, the answer is less clear. We still have a lot to learn about this species, as they are notoriously hard to monitor. Their breeding numbers can rise and fall drastically between years in response to weather and prey availability. In this sense, international studies aimed at understanding their movements and population fluctuations across Europe are a key first step.

Figure 4 Short-eared Owls are notoriously hard to monitor and study, and international research on their movements and population fluctuations are necessary © Mark Carmody

Our research provides an overview of Hen Harrier and Short-eared Owl conservation in Europe, bringing together expert knowledge from nine different countries and 23 study populations. By documenting similarities between threats and conservation strategies to these species across Europe, we hope to provide a stepping stone for international collaboration. For organisations fighting to protect these species across Europe, knowing what other populations face similar threats or sharing knowledge on the success and failure of different strategies can help save valuable time and money and make for more efficient conservation. After all, Hen Harrier and Short-eared Owl populations across Europe are highly connected. Conservation efforts need to be just as connected through international collaborations if we are to save these iconic birds of prey.

References

BirdLife International and HBW 2018. Bird species distribution maps of the world. Version 2018.1. VIEW

Bos, J., Schaub, T., Klaassen, R. & Kuiper, M. (Eds.) 2020. Book of abstracts. International Hen Harrier and Short-eared Owl meeting 2019. Groningen, The Netherlands. VIEW

Murgatroyd, M., Redpath, S.M., Murphy, S.G., Douglas, D.J., Saunders, R. & Amar, A. 2019. Patterns of satellite tagged hen harrier disappearances suggest widespread illegal killing on British grouse moors. Nature communications 101: 1094. VIEW

Image credit

Featured image: Male Hen Harrier © Darío Fernández-Bellon