Learning to identify new birds is one of the joys—and frustrations—of bird-watching. Starting out, there are plenty of easy-to-identify birds in one’s own patch—house sparrows, starlings, jays, most titmice, robins. Once those are sorted, a few groups pose interesting challenges that might take years to master—finches and sparrows (little brown jobs), warblers, small waders (peeps), and many gulls, especially in non-breeding plumage.

Venturing further afield, the ultimate challenge for many of us are the pelagic seabirds (large brown jobs)—shearwaters and petrels, winter alcids, divers (loons) and phalaropes—not least because they are often observed in the fog and mist from the deck of a small boat pitching in the waves on an expensive pelagic seabird tour. Even for the experts, species limits are often changing and new species seem to come and go on the official checklists with alarming irregularity.

How many species?

The two, three, four—or is it three?—species of shearwaters in the genus Calonectris are a case in point. The first of these was formally described as Procellaria diomedea in 1769 by the Italian naturalist (and physician) Giovanni Antonio Scopoli [1723-1788]. Scopoli was an expert on the insects and flora of the Alps but also, from 1769-1772, published a series of taxonomic monographs in which he described several birds that he found in collections. His description of that shearwater was rather vague and included no mention of the locality where the specimen was collected. In 1942 the BOU apparently determined that the type locality was the Tremiti Islands in the Adriatic, also known as Isole Diomedee from which Scopoli, presumably, derived the species epithet.

Subsequent specimens that seem to me to be very similar to the one described by Scopoli were formally described as new species: Procellaria kuhli in 1835 by Friedrich Boie; Puffinus leucomelas in 1835 by Coenraad Jacob Temminck; Puffinus Edwardsii in 1883 by Jean-Frédéric Émile Oustalet; Puffinus flavirostris in 1844 by John Gould; and Puffinus mariae in 1898 by Boyd Alexander. I have read those original descriptions and would be hard-pressed to identify those species, even in the hand. Presumably those authors had specimens and localities to inform their decisions about species’ distinctiveness.

Cory’s Shearwater

On 11 October 1880, Charles Barney Cory [1857-1921] obtained a specimen—taken near Chatham Island, off Cape Cod, Massachusetts—of what he thought might be yet another species of shearwater closely related to the previously described species listed above. Intrigued, he “showed it to some fishermen and requested them to procure any birds they might meet with resembling it.” The next day “one of the boats returned bringing a number of birds of this species. The men stated that they had met with a flock a short distance from shore and had shot several and knocked down others with their oars.” In 1881, he described this new species as Puffinus borealis in the Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club.

Cory was an outstanding ornithologist who devoted both his life and his personal fortune to the study of birds. His father had a large and successful import business and left his fortune to Charles to do with as he pleased. From the age of 16 Charles used his wealth to travel widely collecting birds, particularly in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. At 19, he was elected to membership in the Nuttall Club; at 25, he bought Great Island, Maine, to use as a summer retreat and nature preserve; at 26, he was one of 48 founding members of the American Ornithologists’ Union; at 30, he was appointed as (unpaid) Curator of Birds for the Boston Society of Natural History; at 47, he donated his entire collection of 19,000 bird skins to the Field Museum in Chicago when he could no longer keep them at his home.

In 1906, Cory lost his entire fortune, so he began to take a salary as Curator of Ornithology to continue his passion for studying burds. In their first Checklist of North American Birds (1889) the AOU honoured Cory’s ongoing contributions to ornmithology by giving P. borealis the English name ‘Cory’s Shearwater’.

Figure 1. Likely Cory’s Shearwater (left) and unidentified member of the Cory’/Scopoli/Cape Verde group (right) – South Atlantic off Africa, January 2024 © Ian Jones.

I have read Cory’s formal description of ‘his’ shearwater and would probably not have been convinced (in 1881) that this was a new species. Nor was Gerald Thayer [1883-1939] who in 1915 published his dissent in Science with the provocative title ‘The End of Cory’s Shearwater’. He claimed that “It is indeed a token of provincialism on our parts that this remarkable error should have gone for thirty-four years uncorrected. For Cory’s shearwater…was not a new bird, but an old bird with a new name…its nesting-habits and eggs have long been familiar to naturalists…Puffinus borealis is a synonym of Puffinus kuhli, the Mediterranean great shearwater, a common Old World bird which has been well known for generations.” Previously, Godman’s (1907-1910) ‘A Monograph of the Petrels’ had also stated that he could “not find any difference between individuals from the coast of Massachusetts and others from the Atlantic islands.”

Witmer Stone [1866-1939]—a much more experienced taxonomist and ornithologist than the artist/naturalist Thayer—was quick to publish a rejoinder six weeks later in Science: ‘The End is Not Yet!’. For 51 years, Stone was Curator of Ornithology at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. He was also editor of The Auk (1912-1936) and president of the AOU (1920-1923). In that paper, Stone noted that “…the interesting point in all this is that should the bird from our north Atlantic coast be regarded as identical with the Azores form the name Puffinus borealis Cory is the oldest name for it and must be used; while if they are regarded as distinct, then the American bird will still be known by Cory’s name. In either case we shall retain Cory’s Shearwater on our list!”

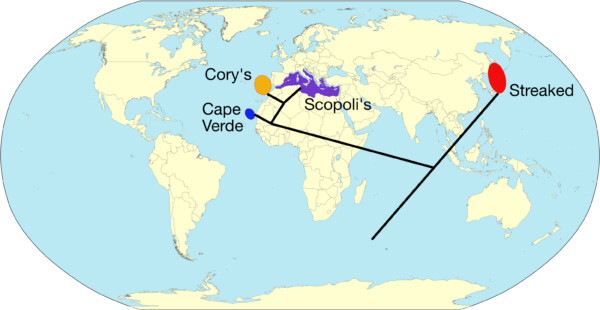

Four species of Calonectris

Recent work looking at mitochondrial DNA and other genetic markers, as well as vocalizations, biogeography, and subtle plumage traits seems to have resolved these issues (e.g., Ferrer Obiol et al. 2022), and there are now four recognized species of Calonectris shearwaters: borealis (Cory’s), diomedea (Scopoli’s), edwardsii (Cape Verde, and leucomelas (Streaked). As Stone so presciently noted more than a century ago “Hasty action like that of Mr. Thayer’s, without the examination of adequate material, is responsible for much of the shifting of names back and forth wlhich has become such an abomination in modern systematic zoology.”

Figure 2. Breeding ranges of the four species of Calonectris shearweaters; species tree with black lines using data from Ferrer Obiol et al. (2022).

Further Reading

Campioni, L., Bolumar Roda, S., Alonso, H., Catry, P. & Granadeiro, J.P. (2024) Colony attendance and moult pattern of Cory’s Shearwaters (Calonectris borealis) differing in breeding status and age. Ibis 166: 925-939.

Cory, C.B. (1881) Description of a new species of the family Procellariidae. Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 6 : 84.

Ferrer Obiol, J., James, H.F., Chesser, R.T., Bretagnolle, V., González-Solís, J., Rozas, J., Welch, A.J., & Riutort, M. (2022) Palaeoceanographic changes in the late Pliocene promoted rapid diversification in pelagic seabirds. Journal of Biogeography 49, 171–188.

Godmanm, F.D.C. (1907-1910) A monograph of the petrels (order Tubinares). London: Witherby & Co.

Nicholson, E.M. (1952) Shearwaters in the English Channel. British Birds 45: 41-55.

Scopoli, G.A. (1769) Ioannis Antonii Scopoli … Annus I-[V] historico-naturalis … Lipsiae: Sumtib. C.G. Hilscheri.

Stone, W. (1915) The End Is Not Yet! Science 42: 530.

Thayer, G.H. (1915) The End of Cory’s Shearwater. Science 42: 308-310.

Image credits

Top right: Puffinus kuhli painting by J.G. Keulemanns in Godman (1907-1910).

Left: Line drawing of shearwaters by Robert Gilmor, from Nicholson (1952).

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here