LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Management actions promote human-wildlife coexistence in highly anthropized landscapes: the case of an endangered avian scavenger. Zuberogoitia, I.†, Morant, J.†, González-Oreja, J. A., Martínez, J. E., Larrinoa, M., Ruiz, J., Aginako,I., Cinos, C., Díaz, E., Martínez, F., Galarza, A., Pérez de Ana, J.M., Vacas, G., Lardizabal, B., Iriarte, I. & Zabala, J. 2021 Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.656390 VIEW

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

How species persist in anthropogenic landscapes is a matter that has attracted ecologists in recent decades. Current landscapes are far from pristine and unaltered areas are usually thought to be home to the most charismatic species. Moreover, the ongoing increase of human need for subsistence resources and aims to connect with nature has transformed landscapes and increased the pressure on species living there. This is the case of Biscay, a small province located in northern Spain which has experienced a profound landscape transformation due to monoculture plantations and an increasing human presence across virtually the whole area. Under this scenario, a small population of Egyptian Vultures (Neophron percnopterus) inhabit and share space with humans in mountainous and rocky areas. The Egyptian Vulture is the smallest and one of the most threatened vulture species inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula. The species has experienced a global sharp decline in recent decades due to human-related threats such as poisoning, collision with human infrastructure, habitat loss and human activities during the breeding season (Sánz-Aguilar et al. 2015; Mateo-Tomás & Olea 2015; García-Alfonso et al. 2021). It is a territorial species that tends to reuse the same territories/nests every year, where they usually raise 1 or 2 nestlings (Serrano et al. 2021). Therefore, one could wonder, how can such a sensitive and ecologically exigent species live and persist within this landscape?

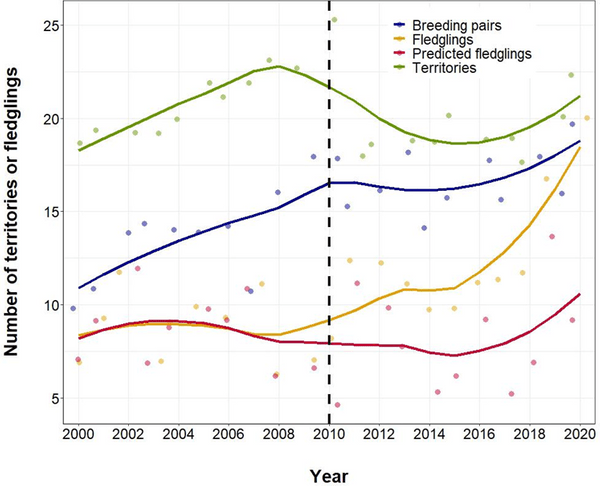

Figure 1 Inter-annual variation in the number of territories (i.e., territorial pairs showing breeding behaviour), breeding pairs (i.e., pairs that lay at least one egg), number of fledglings successfully raised and the predicted number of fledglings that would have been produced without adaptative management. The vertical line shows the beginning of the management actions (2010). Coloured dots represent raw data points. The lines showed the smoothed conditional means.

The answer is simple: the combined efforts of researchers, rangers, stakeholders, conservation practitioners and managers. In 2000, a long-term monitoring project initiated by Dr. Iñigo Zuberogoitia and collaborators intended to evaluate the species’ population status by compiling data of nest occupancy, productivity and by ringing nestlings. Thanks to the data compiled during the first eight years, they discovered that human activities during the breeding season, such as recreational activities and those related to resource extraction (e.g., forestry activities), have detrimental effects on the species’ nest occupancy and productivity, and that such activities varied in their intensity among the monitored nests (Zuberogoitia et al. 2008). Such activities could comprise population viability in the long-term. Thus, it was time to take action. In 2010, thanks to the data and scientific evidence generated, the Biscay County Council implemented a series of measures to address the activities that most often and seriously interfered with the Egyptian Vultures’ breeding (e.g., climbing, races, forestry activities, etc.). At the same time, management actions and a special monitoring protocol for preventing human disturbances in Egyptian Vulture breeding territories were applied. All human activities that could potentially modify the landscape and vegetation around nest sites (~1km radius) required the council’s approval. Management measures consisted of continuous monitoring of nest sites between March to the end of September, therefore, covering the whole breeding season including nest site selection, courtship, egg-laying, hatching, rearing of nestlings and fledging. In 2021, we decided to test whether such actions were effective for the species’ conservation.

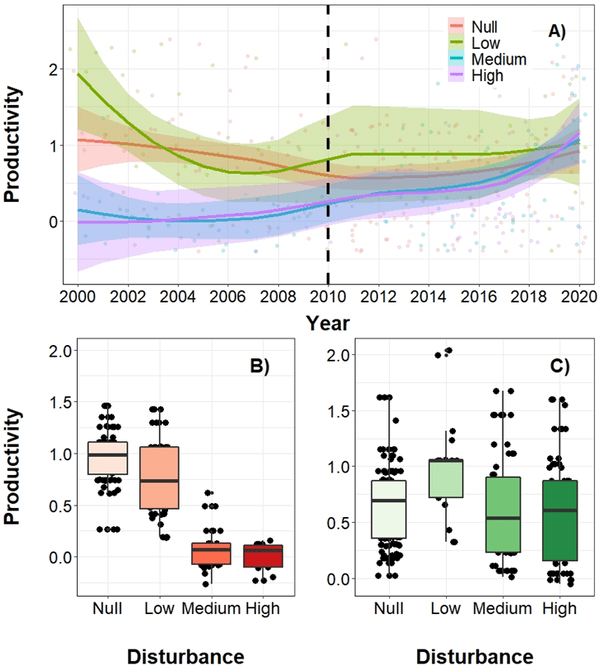

Figure 2 (A) Temporal trends in the number of fledglings per breeding pair (pairs that lay at least one egg) during the whole study period (2000–2020) considering the disturbance regime (null, low, medium, and high) that affected the breeding territories before and after the management action plan. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. The dashed vertical line shows the beginning of the management actions (2010). The (B,C) graphs show the predicted values for productivity (i.e., number of fledglings successfully raised per pair that started reproduction) depending on the disturbance regime before (2000–2009) and after (2010–2020) adaptative management, respectively. Boxplots show the median, the upper and lower quartiles and whiskers indicate variability outside them. Coloured and black dots represent the raw data points in each case.

Was the management effective?

Until 2020, the management action highlighted above proved to be effective in all senses since its implementation in 2010. During this time, the council assessed 5,095 files related to potentially harmful activities during the breeding season and/or in the nest surroundings. This gives an idea of how managers and conservation practitioners could avoid and guarantee species persistence by allowing, banning or displacing such activities in time and space based on scientific evidence. Therefore, contributing to the compatibility of wildlife conservation and human activities of economic importance (e.g., wood extraction). The number of breeding pairs, territories and fledglings increased since the implementation of the management plan. Furthermore, the number of nests subjected to different disturbance regimes increased their productivity thanks to the conservation measures. More importantly, considering the average predicted productivity, 44 nestlings (32.1% of the chicks raised in the 2010–2020 period) would have died if management actions had not been implemented.

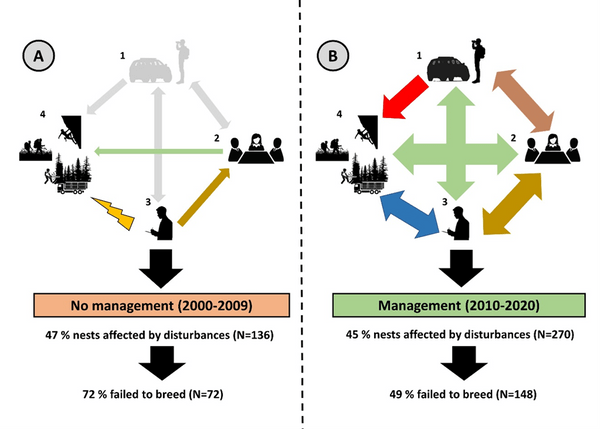

Figure 3 Scenarios showing different collaboration networks among actors involved in the species conservation area. A) A win-lose scenario: socio-economic activities are superimposed to species conservation in an anthropogenic; conservation conflicts occur when not all the actors are involved. B) A trade-off scenario: an equilibrium between socio-economic activities and species conservation exists. The numbers represent each actor involved in conservation conflict and its role: 1) rangers, who are responsible for enforcing conservation legislation; 2) policymakers and managers, who are responsible for environmental laws; 3) ecologist and conservation practitioners delineating evidence-guided-conservation measures and 4) social and economic entities, who are directly and indirectly related in conservation conflicts. The width and direction of the arrows represent the amount and directionality of feedback among each actor involved, respectively.

Coexistence as a seed for conservation success

It is clear that management scenarios in which collaboration among all entities involved is necessary for effective conservation and vulture-human coexistence. Each actor has a fundamental role. Ecologists collect information in the field and translate this to policymakers, managers, and conservation practitioners, which simultaneously transmit this information to rangers, which in tight collaboration with researchers detect, evaluate, and implement management measures in situ. Last but not least, stakeholders adhere to the plan while they are allowed to continue their activity outside sensitive periods and/or at a safe distance not to cause any disturbance. There is, however, a long road for considering this a successful management programme.

As Alexander von Humboldt said, “The most dangerous worldview is the view of those who have never looked at the world.” In the context of our research, this could be interpreted as a lack of some crucial “ingredients” within our recipe. For example, although almost half of the disturbances belonged to forestry and were managed to avoid their impact, others were related to human activities such as hiking, non-managed aerial vehicles, biking and hunting; which are difficult to detect and stop. Targeted campaigns and adequate signalling in both sensitive and non-sensitive places are the way forward to prevent this in the future. These disturbances could, at some point, be avoided once citizens are aware of the problems they can cause with their actions and invite them to take part in the conservation of the species. This could promote and reinforce existing collaboration networks between citizens, researchers, rangers and policymakers to make such coexistence between Egyptian Vultures and humans endure for a long time.

References

García-Alfonso, M., van Overveld, T., Gangoso, L., Serrano, D. & Donázar, J.A. 2021. Disentangling drivers of power line use by vultures: potential to reduce electrocutions. Science of the Total Environment 793: 148534. VIEW

Mateo-Tomás, P. & Olea, P.P. 2015. Livestock-driven land use change to model species distributions: Egyptian Vulture as a case study. Ecological Indicators 57: 331-340. VIEW

Sanz-Aguilar, A., Sánchez-Zapata, J.A., Carrete, M., Beníteze, J.R., Ávila, E., Arenas, R. & Donázar, J.A. 2015. Action on multiple fronts, illegal poisoning and wind farm planning, is required to reverse the decline of the Egyptian Vulture in southern Spain. Biological Conservation 187: 10-18. VIEW

Serrano, D., Cortés-Avizanza, A., Zuberogoitia, I., Blanco, G., Benítez, J. R., Ponchon, C., Grande, J.M., Ceballos, O., Morant, J., Arrondo, E., Zabala, J., Montelío, E., Ávila E., Gonzáles J.L., Arroyo B., Frías O., Kobierzycki E., Arenas R., Tella, J.L. & Donázar, J.A. 2021. Phenotype- and environmental-dependent natal dispersal in a long-lived territorial vulture. Scientific Reports 11: 5424. VIEW

Zuberogoitia, I., Zabala, J., Martínez, J. A., Martínez, J. E. & Azkona, A. 2008. Effect of human activities on Egyptian Vulture breeding success. Animal Conservation 11: 313-320. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus © Jon Morant.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.